‘For when I had by Kentish cloynes the Staffords overthrown, I climbed aloft and thought the king and crown to be my own’

It is midday on Thursday, 18 June 1450, and Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton and his cousin William Stafford are eagerly pursuing rebels in Kent. They ride south through the quiet half-timbered streets of Sevenoaks, leading a small force tasked with scattering a popular rebellion led by a man called Jack Cade.

The air is thick with expectation as Stafford’s column of four hundred retainers slows to let stragglers catch up. The scent of damp earth and summer foliage increases as the contingent gallops beyond the town towards the wooden country of the North Weald. Sir Humphrey has explicit orders to discover the whereabouts of the rebels who abandoned their fortified position at Blackheath under cover of darkness. The king only had to display the royal standard, condemning the rebels as traitors, to make Cade order a general retreat, which fills Stafford with confidence. He concludes the enemy is only a mob of rustics armed with pitchforks and no match for professional soldiers. The chase is on, and Stafford and his men enter Sole fields ripe with summer wheat bordering the Tonbridge road.

There has been no sign of the enemy so far – only an unnatural stillness in the air – and Stafford’s contingent rides on without considering its vulnerability to attack. Sir Humphrey’s valour and impetuosity as a knight are unquestionable. Confident that the rebels are disorganised and retreating, he expects little resistance from the insurgents and concludes they have already dispersed back to their homes.

However, unknown to Stafford and his troops, Cade’s army is concealed, drawing his force ever onward into a waiting ambush. Without warning, the rebels emerge from the woods bordering Sole fields in disciplined ranks, armed with not only farm tools, but warbows, swords and weapons looted from the French wars. They are hardly an inexperienced rabble. Many of Cade’s men are former soldiers, and some are more experienced in warfare than Stafford’s men, who are now caught in a trap.

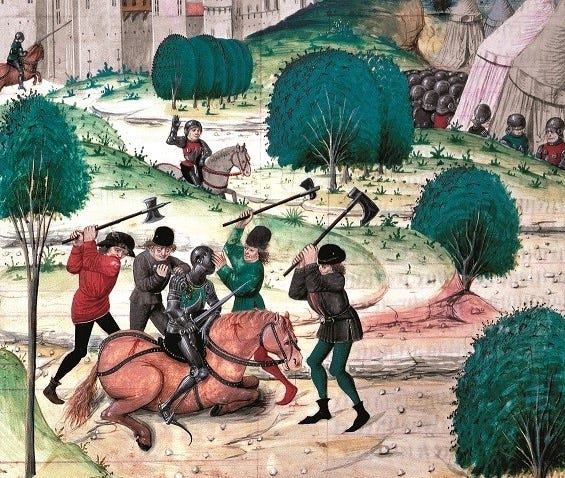

Before Stafford and his men can react, arrows hiss through the air, finding gaps in the royalist ranks. Horses are hit, and their riders are thrown to the ground while Cade’s men swiftly close in. The fight is brief and brutal. Stafford’s vanguard, caught off guard and outmanoeuvred, buckles under the pressure of thousands. The rebels assert their advantage, striking down royal troops as they try to regroup. William Stafford is killed in the confused melee, valiantly taking on more men than he can handle, while Sir Humphrey fights on, wounded, exhausted and bloody. Surrounded and outnumbered, he, too, is soon surrounded and stabbed to death by multiple assailants. His body is stripped, and Cade takes Stafford’s studded brigandine, sallet, and gilded spurs as war trophies.

Seeking to symbolise his triumph, the Kentish captain dons Stafford’s equipment and parades before his men as a mock knight while royal troops are finished off or chased in all directions.

With their leaders dead, some of Stafford’s men manage to flee through Sevenoaks and most escape to tell the tale. The royal defeat is a shocking reversal of fortune. Jack Cade has won an impressive victory and humiliated the king’s forces. With the road to London now open, the rebellion re-ignites, and within days, Cade’s men reach the gates of London, eager to right the wrongs imposed on their county.

The battle of Solefields, fought on 18 June 1450, was a pivotal engagement in Jack Cade’s Rebellion, a popular revolt and precursor to the civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses. Despite its obscurity, the battle marked a significant military reversal for the crown, forcing Henry VI and his well-equipped army of nobles to disperse, leaving London unguarded and open to attack.

The area known locally as Solefields was the place of this important reversal, and today, a plaque commemorating the battle can be found south of Sevenoaks at the junction of the Tonbridge Road. The monument reads, ‘Hereabouts took place on Thursday the 18th of June AD1450 the Battle of Solefields fought between royalist troops under Sir Humphrey Stafford and men from Kent led by Jack Cade.’

Despite the memorial, chroniclers do not reveal the exact location of the battle. However, the fighting likely occurred immediately south of Sevenoaks rather than at Bromley or Tonbridge, which are also mentioned in some contemporary accounts. The evidence suggests that at least two of the leading chroniclers were eyewitnesses to the events of June 1450, although not of the actual battle, and other fifteenth-century sources cited by historians support the story given above.

Medieval England was characterised by political instability, economic hardship, and widespread social unrest among the nobility. The loss of English territories in France during the Hundred Years’ War precipitated an economic downturn, undermining public confidence in King Henry VI’s government. Corruption and maladministration among the king’s ministers exacerbated popular grievances, particularly in Kent and Essex, where these frustrations culminated in a widespread rebellion towards the end of May 1450. Jack Cade (alias Mortimer), a charismatic and politically astute leader, was instrumental in rallying men from Kent in the vicinity of Ashford, and he is generally remembered for demanding governmental reforms in the form of a written manifesto that included removing corrupt officials from the king’s service.

Jack Cade adopted the title ‘Captain of Kent’, and the evidence suggests he was not a simple rabble-rouser leading an unruly mob of commoners. However, little is known about his life before his popular rebellion, although he often used the alias John Mortimer to invoke associations with the noble family of the same name, who had a strong claim to the English throne dating back to Edward III. By aligning himself with the Yorkist cause, headed by Richard, Duke of York, Cade sought to challenge the authority of Henry VI’s government using widespread propaganda in the southern counties of England and across the Thames in Essex. However, due to the limited historical records documenting his early life, Cade’s character and intentions were elusive in 1450 and remain so today.

Some accounts suggest Cade was Irish, while others claim he was born in Kent. He may have worked as a physician, although this is contested, and some sources even suggest he fled to France after killing a pregnant woman. Most of the claims cannot be proven, but Cade may have taken up employment as a soldier. Upon his return to Kent with other disgruntled veterans, he drafted a manifesto called The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent outlining demands for reform. Cade’s proclamation included removing corrupt officials in London, implementing economic relief, and demanding administrative changes, including the reinstatement of Richard, Duke of York, whom the king’s manipulative government had politically isolated in Ireland.

Cade’s organisational skills and persuasive rhetoric enabled him to lead a march on London, a remarkable feat given the inherent risks of treason and the unpredictable nature of arming thousands of people. Before the battle of Solefields, Cade’s rebel army was calculated by Gregory’s Chronicle at some 46,000 men and women, a likely exaggeration given the size of the rebel camp on Blackheath. However, Bale’s Chronicle, which is representative of London opinion in the early stages of the rebellion, records that Cade’s aims started as popular demands and his ‘desires were good, and for the weal of the land’. Therefore, his forces were certainly large by the standards of the day. Many counties like Essex, Surrey and Sussex joined his revolt, and soon Cade’s men reached Blackheath where ‘they made a field, dyked and staked well about’ as if they were at war in France.

Cade’s manifesto flatly called Henry VI to ‘destroy the traitors being about him.’ However, when his plea failed to have the desired effect with messengers sent to discover his intentions, the king decided to adjourn his parliament at Leicester on 6 June and return to London. Several nobles were given commissions to muster their retainers and go against the rebels. But in the end, the king was cajoled by his ministers to confront the rebels personally on 18 June:

The king rode armed at all points from St John’s beside Clerkenwell through London, and with him, [for] the most part, [were] temporal lords of this land of England in their best array. After that, there [came] every lord with his retinue, to the number of 10,000 persons, ready as [if] they all should have gone into war in any land of Christendom with bends above their harness [so] that every lord should be known from [each] other.

As stated above, the king’s men were marked with a heraldic symbol to avoid confusion with the rebels. An English Chronicle edited by Davies states there were 15,000 men with the king, including contingents supplied by the Duke of Buckingham, the Earls of Northumberland and Norfolk, Lord Rivers, Scales, Grey and other prominent English knights. Their retinues were well-equipped, we are told, with men-at-arms and artillery, but when they arrived at the rebel camp at Blackheath at daybreak on 18 June, they found it deserted. Cade’s rebels had fled in the night, it seemed. Therefore, that same morning, Sir Humphrey Stafford (c.1400-1450) was given command of the royalist vanguard (allegedly by Queen Margaret) with orders ‘to spy where the Kentish men were’. Some writers suggest Stafford was sent to disperse Cade’s men and, if possible, capture the ring leaders, but it seems the royalists were drawn into a battle either by chance or their own foolishness:

And in the forward, as they would have followed the captain, was slain Sir Humphrey Stafford and William Stafford, squire, one [of] the manliest men of all this realm of England, with many more other men at Sevenoaks in Kent in their outraging from the host of our Sovereign Lord the King.

At first sight, this ‘outraging’ (or outranging) from the king’s host seems a peculiar word to use in a chronicle unless the writer is suggesting that Stafford was impetuous in some way. According to Gregory’s Chronicle, his contingent comprised only 400 men, even though it was well known that the rebel army numbered thousands. Therefore, what happened at Blackheath to prompt such a rash move into the unknown? Even though Cade’s men may have been considered ill-disciplined, the military significance of splitting the royal army must have been evident to everyone. To ascertain the rebels' whereabouts can be understood, but to go on the attack and try to capture Jack Cade seems impossible – a factor that smacks of knightly pride rather than prudent strategy.

Sir Humphrey Stafford was a loyal servant of King Henry VI and a kinsman of the Duke of Buckingham, who held extensive estates in England. Humphrey served as Governor of Calais for a time, and he married Eleanor Aylesbury, who was later buried alongside her husband in St John’s Church, Bromsgrove. At the time of Jack Cade’s Rebellion, Stafford was about fifty, and along with his cousin William Stafford of Southwick, they likely followed orders but got too close to the enemy in the end.

When Stafford and his men ran headlong into the rebel ambush at Solefields, they soon realised that Cade’s men were seasoned soldiers hardened by years of war in France rather than poorly armed rustics. Some rebels had likely been recruited from the land, and the mention of pitchforks in the battle indicates the presence of farm labourers. But many knew how to obey orders, and they soon surged forward en masse, aiming for those royalists in command.

William Stafford fought valiantly, if recklessly, sources tell us, but the royalist force was quickly overwhelmed by Cade’s men, and the Staffords, along with 140 others, were killed. One chronicler says that one of the Staffords would not yield ‘but fought with a two-handed sword on horseback, and one with a pitchfork bare him out of his saddle, where he fought on foot till he was slain [with] twenty-seven more.’ According to sources, Sir Humphrey Stafford’s studded brigandine and expensive accoutrements were stripped from his dead body. And it is said that Jack Cade ‘to advance his pride, he did [put] upon him the brigandine of the aforesaid Sir Humphrey of velvet garnished with gilt nails, and his sallet and gilt spurs, and so of a knave was made a knight, where after he then with his people drew toward London.’

The Staffords’ deaths and the royalist retreat after the battle symbolised the crown’s inability to respond effectively to ordinary people’s grievances, and this was recalled in horror by an eyewitness present on Blackheath when ‘a sudden shout and noise upon the said [Black] heath’ was heard when news arrived of the rebel victory at Solefields. In fact, the upshot of Cade’s victory was that the rebellion was deemed capable of further success. The rebels had won against all the odds, which polarised men’s attitudes and morale in the royal camp, so much so that Henry VI deserted his army. A general retreat was ordered ‘after divers lords men drew them thither on the Blackheath and said that they [had seen] their friends slain, and that they were like to be slain also if they followed the king and his traitors.’ In fact, the panic was so great that on 19 June, many discontented royal retainers threatened to join the rebel ranks unless several royal servants regarded as traitors were arrested immediately.

At this point, even Henry VI, then at Greenwich, had no option but to comply with Cade’s demands of arresting certain ministers, including Lord Saye, who was put in the Tower for his safety rather than his crimes.

The battle and aftermath had serious consequences, and the king’s ineptitude to satisfy the rebels, or put down the rebellion, played a significant role in the events that followed. Military losses in France characterised Henry’s early reign, and his inability to manage this reversal and his kingdom during a crisis exacerbated domestic tensions. Corruption among his advisors, like the infamous Duke of Suffolk, who was executed in May 1450, Lord Saye and others, created widespread unrest and division in England. While Henry was known for his piety and gentleness, these qualities were soon seen as weaknesses by those nobles who were ambitious or craved the throne. Strong kingship demanded strong leadership, and Jack Cade’s Rebellion was one of many uprisings during Henry’s reign, which contributed to unrest, political feuding and in a few years, civil war.

Today, the battle of Solefields is a largely forgotten episode preceding the Wars of the Roses. Despite the mutiny of the king’s men at Blackheath, which was one of the most critical events of Cade’s Rebellion, the proximity of the rebels so close to London immediately polarised the capital. Many people welcomed the rising, and those who did not questioned their loyalty to Henry VI when the king and his council fled north, leaving London to an uncertain fate.

To be continued…

If you enjoyed this post, leave a comment. In the meantime, if you are a fan of the Wars of the Roses, here are some of my latest books on Amazon. Reviews are always appreciated!