A Wars of the Roses battlefield is a strange place to find a court official who was otherwise employed at ceremonial, civil and chivalric events - but this is precisely the case if we dive into the secret world of heralds.

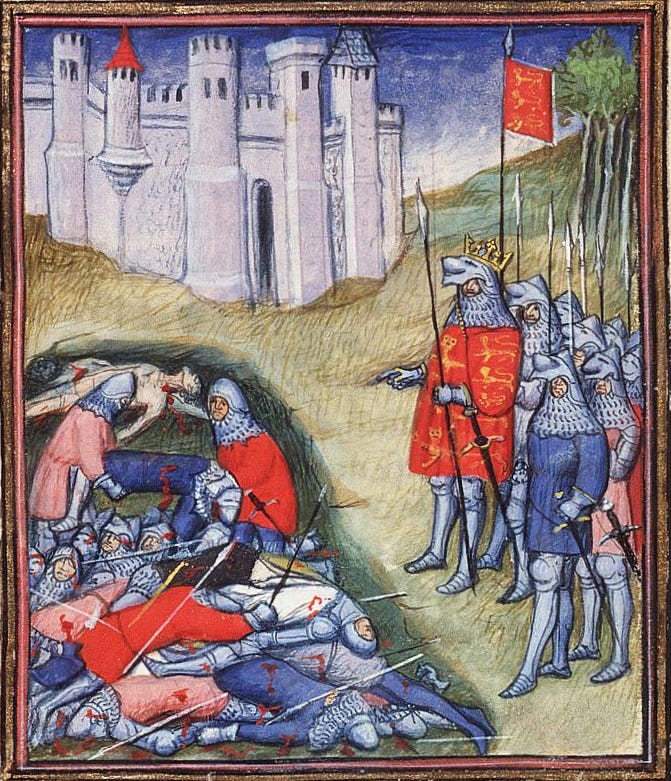

English heralds (and especially military heralds) were present as non-combatants at many battles during the medieval period despite the unchivalrous way the nobility conducted themselves in the confused fog of war. Their presence was quite astonishing during the Wars of the Roses because chivalry, as it was then traditionally understood, had no firm foundation between opposing nobles as it had in the Hundred Years War. It is known from contemporary sources that the higher classes were slaughtered at will (or executed) on the battlefield despite ingrained precedents of mercy or ransom. Therefore, I thought I’d take a look at the career of one herald in particular who likely saw the face of battle on many occasions. This article is part of something I’m working on at the moment that questions if, due to the records heralds produced for their masters, they were, in fact, the first war correspondents of the pre-modern era.

Kings of Arms, as some senior heralds were called, delivered important (and sometimes secret) messages between kings and nobles. They compiled narratives and chronicles for their benefactors, and with the aid of pursuivants, they noted the presence of combatants during battles, recorded casualties and even organised the burial of the dead after battles had ended – a grisly task, to say the least, for such learned and artistic individuals. It is well-recorded that heralds had developed their trade throughout the medieval period, and their presence at tournaments and ceremonial events is probably where we know them best.

As discussed, the main function of heralds was to act as messengers between nobles and primarily to observe and record chivalric deeds along with the ancestry of noble families. Court cases could result from the replication of heraldic achievements, and this was a common occurrence in the Middle Ages because heraldic devices were used to distinguish man from master. This was displayed on the banners and standards of the nobility and, before the Wars of the Roses, on their shields and tabards. The symbology was an art form in itself and still is, and in the Middle Ages, the giving of arms had to be regulated to stop the bogus inheritances of wealth and property, the heralds acting as judge and jury if necessary if arguments arose from duplication or fraud.

Great nobles had their own specific heralds and pursuivants. Certain areas like the north had their nominated officials, and chief of all the heralds in England during the Wars of the Roses was a man called ‘mr gartier Smyrte’ who was, as his title suggests, Garter King of Arms (of the Order of the Garter) from 28 March 1450 until his death in 1478.

John Smert (Smart) was the son-in-law of William Bruges, the first Garter King of Arms, who was appointed to the position on 5 January 1420. William had served both Henry V and Henry VI on diplomatic missions abroad on many occasions, but he was first and foremost a man who acted as a go-between, sometimes on delicate matters. Burges attended Henry V’s wedding to Catherine of Valois in 1421, and he officiated at the king’s funeral the following year. He also produced the Bruges Garter Book in about 1430, the earliest armorial book of its kind, and on his death in March 1449/1450, John Smart acquired his title through ‘a smart’ move and marriage to Bruges’ daughter Katherine, although it is recorded that Smart married twice in his life.

John Smart’s parentage is unknown. The chronicler Phillipe de Commines thought wrongly he was a native of Normandy, but Smart apparently owned land in Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire, so his family may have been from that part of the country. Apparently, he had been a lawyer before being appointed a notable pursuivant, and soon after being appointed a herald, he was sent to Burgundy in 1444 on various diplomatic missions as ‘Guyan pursevant’ for Henry VI over the next five years. Smart was named again as Guyenne Herald by Henry VI on 3 April 1450 and was reappointed to this position by Edward IV on 1 March 1462, meaning Smart likely filled two roles in the Wars of the Roses, for which he received a stipend (fixed regular sum) of £40 a year for his services, a considerable amount of money in the fifteenth century.

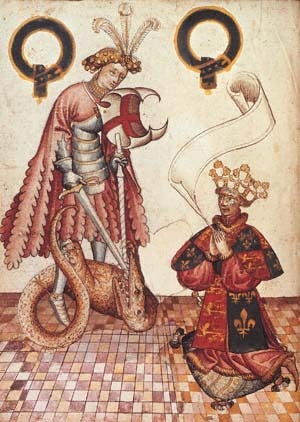

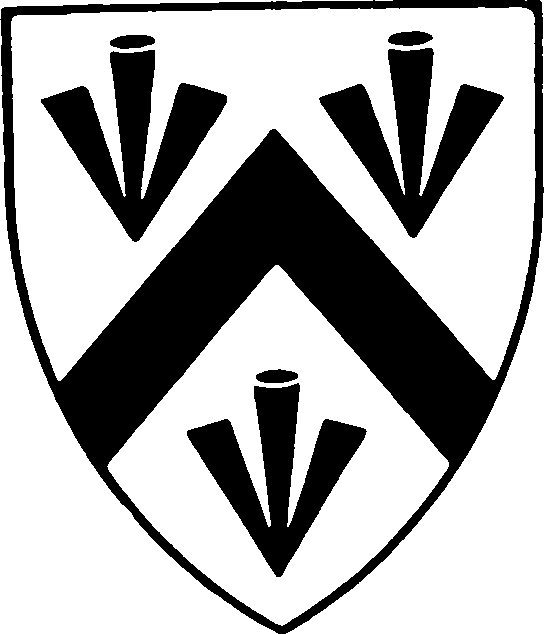

As depicted above, John Smart presents himself within the initial ‘A’ of the grant of arms he authorised for the Tallow Chandlers’ Company in 1456. He is depicted wearing the quartered English royal arms on his tabard and a golden crown, although this crown is less ornate than some heralds. Smart is standing upright, pointing his right index finger upwards while his left hand holds a wand directed at the new coat of arms he authorises. The image portrays Garter as an authoritative figure who has the king’s permission to grant arms, and Smart’s depiction of himself probably inspired later heralds to include similar images of themselves in the initial letters of grants of arms that they confirmed.

In 1459, John Smart (as ‘garter kyng of Armes’) appeared in a letter dated 10 October sent to Henry VI by the Duke of York, the Earl of Warwick and his father, the Earl of Salisbury, after the latter’s Yorkist victory at Blore Heath. Smart had been sent to the king to plead the above-named lord’s innocence before the Yorkist encounter with the king’s forces at Ludford Bridge:

And syth that tyme [taking solemn oaths], we haue certyfyed at large in wrytyng and by mouthe by Garter kyng of Armes, nat only to youre sayde hyghenesse, but also to the good and worthy lordes beyng aboute youre moste noble presence, the largenesse of oure sayde trouthe and dewte, and oure entent and oure disposicione to seche alle the mocions that myghte serue conuenyently to thaffirmacione therof, and to oure parfyte suertees from suche inconuenient and unreuerent geopardyes, as we haue ben put ynne diuerse tymes herebefore.

However, on this occasion, Smart’s words fell on hollow ground. Soon after hearing what York and his followers had to say, treachery in the ranks caused the Yorkists to flee into exile, and no doubt Smart (and his fellow heralds) were soon wondering how they could function as officials in a civil war where no one could be trusted or follow the chivalric code. Indeed, in the following year (1460), Smart is also mentioned in a record of payments accounting for heralds who were in arrears, proving the government was straining under the various pressures of civil war and a financial crisis.

In the turmoil of the winter campaigns of 1460, it is possible that John Smart was among the various ‘Harralds’ present at large-scale battles such as Mortimers Cross, the second battle of St Albans and Towton in 1461. The recording of immense casualties at the battle of Towton must have come as a complete shock to those who witnessed the carnage, and the fact that executions were becoming regular occurrences on both sides likely kept heralds busy with records and the changing face of their arms. Previously, in the Hundred Years War, ransom had been commonplace among the nobility. However, now the opposite was in fashion and treason against the king legally meant that the state condoned this. Thankfully, John Smart and his fellow officials were exempt from the violence of the Wars of the Roses; they got paid for their services and no doubt made a good living out of noble killing noble due to treason and feuding.

There is evidence that some late medieval heralds owned military texts. John Smart, for instance, owned a copy of the English prose translation of Vegetius’ De re Militari, which discusses the tactics and logistics of Roman armies. Proof, if any was needed, that Smart was well-versed in military matters, not just ceremonial and heraldic duties. The book initially belonged to the Chalons family, and it is suggested that the book might have come into Smart’s possession through his father-in-law, William Bruges, as Bruges was connected to Sir John Chalons in 1446.

After 1461 and Edward IV’s accession to the throne, John Smart was employed again as a diplomat, especially in Scotland and Burgundy. He attended the marriage of Princess Margaret to Charles the Bold in 1468, and between these dates, he was still being paid £40 for his services. In 1469, he was sent on a Garter mission to the Duke of Burgundy, but in 1470, he was back in England again to witness the treacherous exploits of dissident Yorkists who had turned on Edward IV. After the rebellions in the north, the king sent Smart as Garter King of Arms to order the Duke of Clarence and the Earl of Warwick to attend and answer accusations of treason against the crown. But again, the actions of ambitious men like Warwick and Queen Margaret of Anjou decided the course of history despite Smart’s official heraldic overtures of clemency to the Kingmaker.

After the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury, Fauconberg’s rebellion and Henry VI’s death in 1471, England saw a period of peace for a time under Edward IV. In October 1472 it was said ‘Mr Garter Smert was suffering an impediment in his tonge’ and on a state occasion ‘Mr Norroy [King of Arms] cryed ye larges in the hall’ for him. According to sources, Smart had lost his voice and may have suffered a minor stroke at the time. But there is no way of knowing the results of the ‘impediment’ other than Smart was undeterred as an active herald. He is mentioned in Edward IV’s 1475 muster to France, along with other heralds, where he personally delivered several vital messages to the King of France that resulted in the Treaty of Picquigny.

At one time, Smart seems to have been living in the parish of St Bride’s, Fleet Street, where we learn his house had a garden. He may have died here sometime before 16 July 1478 (although this is uncertain). However, on this date, his successor, John Writhe, was appointed Garter King of Arms, and we may be sure this was a profession for life and that Smart had made his last announcement as a herald in Edward IV’s reign.

It may seem strange that heralds were still used militarily in civil war, but their involvement was nonetheless widespread. Smart was only one of the many heralds and pursuivants who rose from humble beginnings to play vital historical roles. Their various oaths bound them not to commit perjury when recording events and casualties at battles. We may wonder at the pressures their benefactors put them under due to propaganda, but most, including Smart, went about their business despite the treachery and bloodletting of the Wars of the Roses. Their presence was necessary, it seems, to condone the art of war in some way, and this is how we must see them, or they would have never survived into the modern era.

If you enjoyed this post, let me know. In the meantime, if you are a fan of the Wars of the Roses, here are some of my books on Amazon.

My new book, The Rose, The Bastard and The Saint King, is out on 21/11/24. You can pre-order it now from all the usual places.