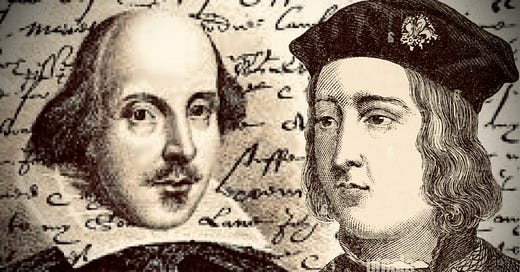

The Missing Monarch

Or, why Shakespeare never wrote Edward IV: Exploring the artistic and political reasons behind the Bard's much overlooked king.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE is known for his history plays, and he wrote about the tumultuous period known as the Wars of the Roses with bloody and highly political gusto. In doing so, he featured several monarchs who fit the much-skewed Tudor viewpoint of history well, and consequently, fact was substituted for fiction on many occasions. Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, and Richard III gave Shakespeare ample dramatic scope to explore how unstable the past had been before the Tudor period. However, neither Shakespeare nor his contemporaries ever wrote a play entitled Edward IV, despite his crucial role in the Wars of the Roses as a strong English king, and this has bugged me for some years now.

Thanks to Shakespeare, the real Edward IV intentionally and literally disappears somewhere between the cracks of Henry VI, Part 3 and Richard III. Obviously, Edward appears in the two plays, but he is presented as a shallow, fickle man, first overshadowed by the grandiose and politically astute Warwick (The Kingmaker), and then much-weakened, he ends up exploited by his ‘villainous’ brother Richard III to the point of death. In short, Shakespeare added Edward IV reluctantly to his plays, and several factors may explain the reason why:

1. Edward IV's Role in Shakespeare's Existing Plays

Edward IV's story is already integrated (intentionally) into Henry VI, Part 3, and Richard III. Edward plays a central figure in these Wars of the Roses stories, rising to power as the Yorkist king and eventually securing his throne by defeating the Lancastrian forces at Towton. In short, Shakespeare may not have felt the need to write a play about Edward IV because his narrative was already deeply embedded in the broader scope of his other historical dramas. Moreover, while significant, Edward IV's reign did not have the dramatic arc of downfall or extreme internal conflict that Shakespeare often favoured.

2. Shakespeare's Focus on Tragedy and Conflict

Shakespeare was drawn to stories of intense personal and political conflict, often with tragic consequences. While Edward IV's reign was not without its challenges, his story lacks the same dramatic tension found in other historical figures such as Richard III or Henry V. Edward IV was a successful and charismatic king who, after securing his throne in 1461, reigned relatively peacefully compared to the civil wars and rebellions of his predecessors and successors. Therefore, after gaining the throne, his reign may not have provided the same fertile ground for Shakespeare's interest in tragedy and moral complexity.

3. Richard III as the Culmination of the Wars of the Roses

In his play Richard III, Shakespeare portrays the ‘final act’ of the Wars of the Roses, focusing on the villainous rise and fall of Edward IV's little brother. This play serves as a kind of dramatic conclusion to the dynastic struggles between the houses of York and Lancaster. Shakespeare may have seen Richard's story (and 1485) as the natural climax of the era, with Edward IV's earlier successes paving the way for Richard's treachery. Therefore, in this context, Edward IV’s reign is perhaps a necessary background rather than a standalone narrative.

4. Popular Demand and Theatrical Constraints

Another reason Shakespeare might have omitted Edward IV in his canon of histories is seen in the tastes of his audiences and the theatrical constraints of his time. The Tudor-Elizabethan public had a strong appetite for stories of dramatic conflict, treachery, and the personal flaws of kings, as evidenced by the success of his plays about Richard III, Macbeth, and Henry IV. Edward IV, despite his importance, may not have offered the same dramatic appeal despite bringing peace to England for twelve years. In short, Edward's story lacks the heightened sense of personal downfall or intense internal conflict that Shakespeare often used to captivate his audiences.

Additionally, the length of his historical cycle may have discouraged Shakespeare from dedicating another play to the Wars of the Roses. By the time he wrote Richard III, Shakespeare had already chronicled the conflict in multiple plays. Therefore, he might have been more interested in moving on to new subjects (like Henry VIII) rather than revisiting a king whose story had already been partially told.

5. Historical Sources and Tudor Propaganda

Shakespeare's history plays were heavily influenced by his sources, primarily Holinshed's Chronicles (and others) of doubtful historical credibility. These sources, often shaped by Tudor propaganda, tended to focus on figures that would bolster the legitimacy of the Tudor dynasty. Edward IV, while necessary as a character in the Wars of the Roses, may not have been emphasised as much in these chronicles compared to figures like Henry VII (who, despite further Yorkist rebellions, ended the conflict and founded the Tudor dynasty). Shakespeare, writing in the reign of Elizabeth I, the last Tudor monarch, would have been sensitive to these political undertones and may have favoured figures whose stories aligned more closely with the Tudor narrative of an England with a past fraught with civil war and political instability.

In conclusion, Shakespeare's decision not to write a play titled Edward IV likely stemmed from artistic, narrative, and political factors. Edward IV's story was already woven into Shakespeare’s other history plays, and his reign lacked the intense personal conflict or tragic downfall that Shakespeare favoured. Moreover, with the Wars of the Roses culminating in his Richard III, Edward IV's story may have been seen as only a chapter in a much larger narrative rather than a subject deserving of its own play.

6. Edward's role as an illegitimate king

Lastly, Shakespeare knew of the claims surrounding Edward IV’s real or supposed bastardy. In fact, he includes them in Richard III where speeches by the Duke of Buckingham echo historical claims by contemporary chroniclers. When Edward dies, his children, especially the two Princes in the Tower, are similarly tarnished according to historical precedent, and this is how Richard ascends the throne. Therefore, Shakespeare may have also taken the same view as his sources and aimed to touch on Edward’s illegitimacy but not labour the subject. Alternatively, Shakespeare may have thought a single play about Edward IV would not be favoured by his benefactor’s political outlook, which is why the play was never written.

According to the real bastardy claim, Edward was not a legitimate King of England. Renaissance culture was deeply concerned with the concept of legitimate birth as the basis for claims to property and royal succession, and Elizabeth I was well aware of how her family had manipulated these claims in the past. Therefore, Shakespeare may have been constrained when writing about bastardy and portraying Edward in his Wars of the Roses plays.

So much for reality!

However, in my view, Edward IV can hardly be a bit player in a drama, and much is left out of his real story in the existing narratives of Henry VI and Richard III. Therefore, for a bit of fun, and from the long-lost archives of The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, I humbly present the first scene of The True History of Edward IV: Shakespeare’s Lost Play in several parts to be continued hereafter:

THE TRUE HISTORY OF EDWARD IV:

SHAKESPEARE’S LOST PLAY

Act I, Scene I Ludlow Castle. Enter young Edward of Earl March holding a white rose. Edward: O England, fairest jewel of the earth, Thy verdant hills, thy rivers’ silver gleam, Thy towns where ancient spires kiss the sky, How bright the stars that crown thy blessèd isle, How free the winds that course across thy fields, All stir my heart with pride and fierce resolve. Yet, ’neath this tranquil visage, shadows lie, And whispers of villainy taint the breeze. Shall we, who spring from noble Edward’s line, Stand idly by while factions tear thee down? O no, it cannot be, it shall not be! For in this breast beats royal blood and true, And in these veins England’s hope resides. Not for ourselves, but for our king we strive, To cast aside the fear of inward war, And lift the banner of our just renown. (he looks from the window) When spring’s soft breath doth kiss the waking earth, And flowers bloom in beauty ‘cross the lea, Then shall our swords, in righteous cause, arise, To guard the peace that others defile? Though dark the path that lies before us now, And heavy hangs the threat of strife remains, Yet shall we march, with Heaven’s favour armed, To see our England freed from traitor’s chains. (he puts the rose in his button hole) Enter the Duke of York. Duke of York: Now, Edward, lend thine ears unto thy sire, For shadows ‘cross our noble house do creep. (he shows Edward a letter) This privy note doth say proud Somerset, with serpent’s guile, Doth again wind coils ‘round Henry’s feeble brow. His honeyed tongue doth shape the king’s decrees, And bends them ‘gainst our cause and England’s weal. Edward: My lord, what perils doth this wily Beaufort, Prepare for us and this fair land? Duke of York: Know’st thou, my son, when wolves in counsel sit, On lambs who quake in defenseless folds. This Somerset, with treach’rous whisperings, Doth sway King Henry from the path of right. He plants suspicion ‘gainst our loyal name, And seeks to sever us from England’s heart. Edward: But can such wiles unfix the nation’s peace? Are King Henry’s eyes so veiled in trustless dark? Duke of York: Aye, trust is Henry’s flaw and his undoing. In Somerset he sees a faithful friend, Whilst we, who’d steer the realm with steady hand, Are painted black with falsehoods cheap. The crown itself adorns a puppet’s brow, And in Somerset’s ill-fingered grasp it sits. Edward: What course, then, shall we take, my noble sire? Shall we await the storm or seize the helm, From those who conspire our deaths? Duke of York: To tarry is to court our swift destruction, Yet, neither rashness shall our safeguard be. We must, with craft and cautious stratagem, Unmask this Beaufort ‘fore the kingly court. Expose his treachery to all men’s eyes, And thus reclaim our honour and our right. Edward: (draws his sword) Then let our deeds speak louder than our tongues, For in this struggle, justice is our sword! Duke of York: Well said, my son, thy spirit doth us proud! Prepare thyself, for in the coming days, We’ll test the mettle of our noble house. This Somerset shall find, to his dismay, That Yorks are not easily displaced this way. Enter the Duchess of York, agitated and faint with fear. Duchess of York: My lords, forgive this sudden, troubled breach, But dark forebodings vex my restless mind. This very night, whilst sleep embraced mine eyes, A vision fierce and dreadful seized my soul. Duke of York: What spector of the night hath brought thee here, With visage pale and heart so full of dread? Duchess of York: I dreamt of war’s cruel hand ‘cross England’s fields, Of blood-stained swords and cries of universal despair. I saw thee, husband, ‘midst the fray’s harsh storm, Thy noble form o’ertaken by the foe. In snow so pure, yet tainted with thy blood, Thou fell, and darkness claimed thy breath and life. Edward: O mother, what grim tale dost thou unfold? These visions are but workings of the night, And hold no power ’gainst our steadfast hearts. Duke of York: Peace, Edward! Dreams oft’ bear a deeper truth. Dear wife, thy fears do pierce me to the core. Yet, know that fate is but a malleable clay, And we, the sculptors of our destiny must shape, Fortunes wheel and life's torturous way. Duchess of York: (embraces her husband) But beware the path that leads to war’s embrace, For in its arms lies naught but death and woe. I beg thee, York, tread with care and might, Lest this dark vision come to rueful light. Duke of York: Thy counsel, dearest, shall not go unheard. Yet justice calls us to defend our name, And save this realm from Somerset’s deceit. We march with prudence, and with Heaven’s grace, We’ll turn these omens to a brighter fate. Duchess of York: Then may the angels guard thee in this quest, And turn the tide of doom to hope’s fair shore. My heart doth pray for peace, for thee, for all. Enter Lovelace, a Kentish squire, who bows low to York. Lovelace: (breathless) My lords, my lady, humbly do I come, From thy worthy brother Salisbury in the north, To serve and aid in all your noble aims. Pray, is there aught that I might undertake, To ease your burden or speed your task? Duke of York: Lovelace, thy service is a constant boon, And well we know thy heart is true to York. But what news from our prudent Neville brother, And how fairs he and the Percy lion his constant thorn? Lovelace: My lord of Salisbury is beset with enemies on all sides, Egremont Percy and Exeter in arms are together plight. And for this cause Salisbury waits upon your clarion call, To right the wrongs of this fair land. Duke of York: Then attend us now, as we prepare to face, The trials that the coming days may bring. Lovelace: (kneels before York) With all my soul, I’ll follow where you lead, My gracious lord, test me to extreme. For in your triumph lies my humble gain. To serve is my willing way. (aside) O Somerset, thy bidding I obey, And with my cunning shall I weave my way. Duke of York: Come, Edward, let us hence, our plans to lay, For much awaits in our beleaguered land. Lovelace, ensure your men of Kent are well prepared. And fear not dear wife for our safe return. For soon we march to set our nation right. And save our king from Somerset’s slight. Lovelace: It shall be done, my lord, with utmost care. Exeunt the Duke of York and Edward. Duchess of York: O fickle fate, be gentle to my love, And spare his life from war’s devouring maw. For in his valour lies our family’s strength, And England’s hope guides his unfaltering hand. Exits weeping. Lovelace: (aside) Go then, weep for York and Salisbury both, Soon they will feel my dark intent. O treachery, thy cloak doth hide me well, And in the shadows do I weave my plot. For Somerset, my true allegiance stands, And York shall fall by these, my hands. Exit.

To be continued…

Do you think Henry VII, and probably more so Edward IV, are not as well known in the public consciousness because they were not giving the big Shakespeare treatment?

You would think Shakespeare would have doted on Henry VII, but, again, he was going for the big audience when he bigged up Richard III. Consequently, Henry was left at the thorn bush scratching his head.