If 28,000 men were killed at the battle of Towton in 1461 where were their remains buried? Who buried them, and what effect did such a massive death toll have on the hearts and minds of the population?

These questions always crop up when I meet anyone interested in arguably the bloodiest battle on British soil. Most of these questions are, in part, linked to human nature. Some people are naturally curious. Others are trying to understand the unusually high casualties given by the heralds after the event. Historians question the actual proportions of the battle as a percentage of the death toll. But most people, I have found, are generally astounded by what actually took place in such a relatively small area of Yorkshire in 1461. They instead question the trauma that affected those who participated in the battle and those who had to deal with it after.

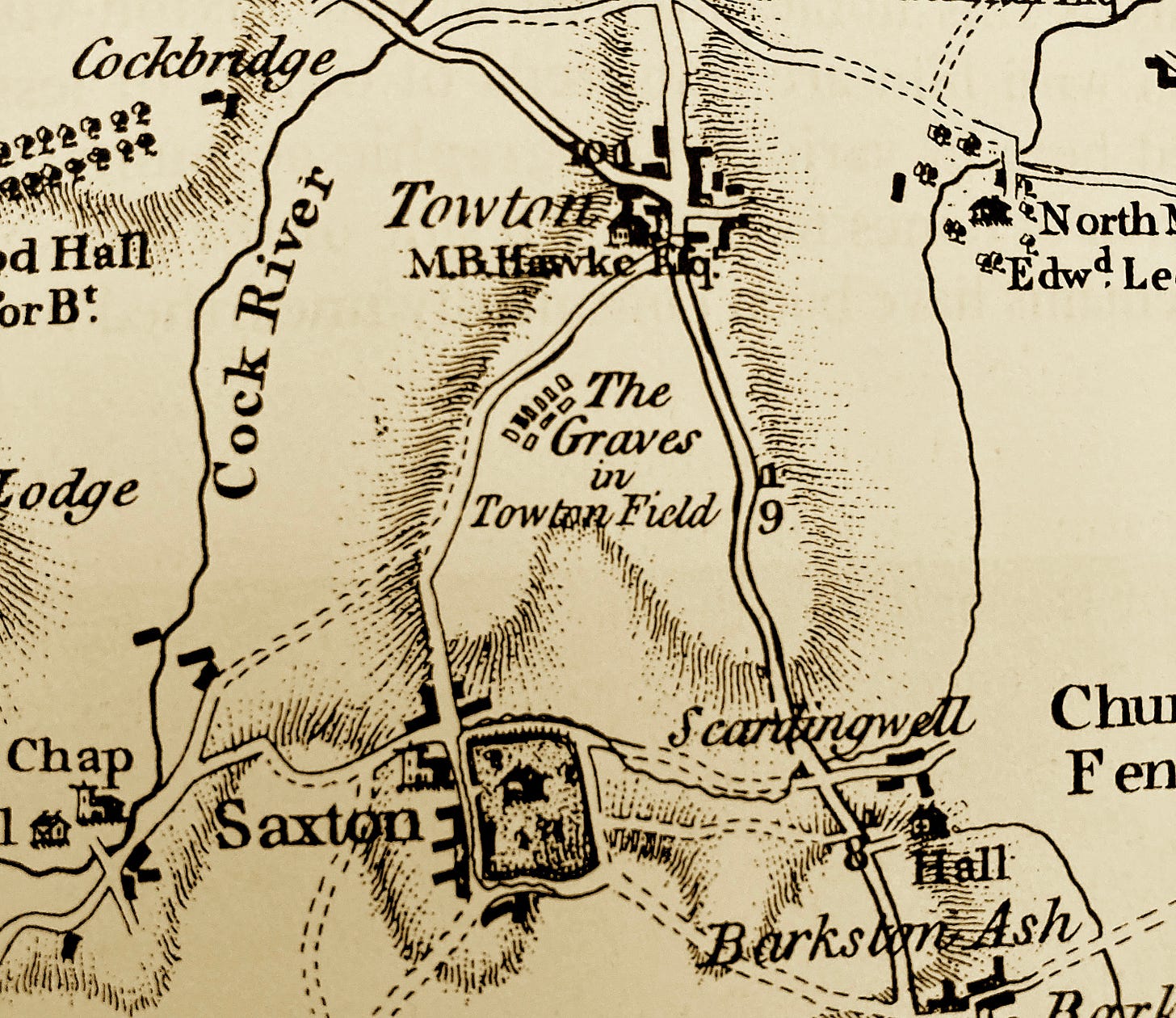

Documentary and archaeological evidence prove that human bones have been found for centuries on the battlefield. Significant amounts of soldiers were buried (or later reburied) in the two nearby villages of Towton and Saxton when the area was cleared. The evidence for chapels of ease both at Lead and Towton is wholly conclusive, and the parish church at Saxton was perhaps the obvious location to afford some of the dead a decent burial in consecrated ground immediately after the battle ended (Lord Dacre being the most obvious of these). However, the questions raised by the Towton dead lead to several other questions, not least, the important matter of how medieval battlefields were dealt with in the fifteenth-century and if all the dead were given proper burial rites.

The key question here is obviously the number of men killed (and also cut down in the surrounding countryside during the rout). But part of the answer in Towton’s case can be found in a contemporary document that contains an important clue. This edict, issued by Richard III a year before he was killed in battle at Bosworth, is testament to the much-maligned king’s faith and powers of reconciliation. He recalls how those that fought,

…were cut off from this human life, and their bodies put in three pits in the said field and other nearby places completely without any Christian burial, as is well known, wherefore we, deeply sorry that the dead should be buried in this way in these last months have caused their bones to be exhumed and given Christian burial, partly in the parish church of Saxton in our said county of Yorkshire and its cemetery, and partly in the chapel of Towton and in its surrounding. (i)

Therefore, according to this evidence, the simple truth is that a vast amount of the Towton dead did not receive proper burial according to the accepted religious practices of the day.

It is well documented that a large proportion of the Towton dead were drowned in the River Cock when the Lancastrian line broke and they rushed headlong down precipitous slopes bordering the battlefield. Others perished in the much larger River Wharfe hounded by the Yorkists who pursued them towards York. Also, a significant number of bodies were buried in mass graves on the right-hand side of the road leading from Saxton to Towton (see map above). But it is clear that King Richard, at least, thought it un-Christian to leave so many souls ‘unshriven’ on a battlefield, and this is one reason why there are no longer any mass graves where the actual fighting took place.

No doubt, Richard’s proclamation was the main reasons why ‘the Graves in Towton Field’ were disturbed. Another reason may be due to the enlargement of Saxton and Towton fields during the Tudor period. Bones and remains from other graves were probably coming to the surface by this time. But a further reason for the removal of bodies after the battle is perhaps more obvious: some families would have wanted to bury their loved ones elsewhere, as in the case of Lord Welles of Methley.

Clearing the battlefield and local rivers was clearly a priority for local villagers around Towton. According to the sources, rivers were wholly contaminated with ‘bridges of bodies’ and disease from rotting corpses could not be avoided. Therefore a massive job lay ahead for the villagers and others paid to carry out the grim task. The dead were spread, ‘six miles long by three broad and about four furlongs’, according to George Neville Bishop of Exeter, therefore, large numbers could not be transported very far. The Yorkist soldiers would have been totally exhausted on the day of the battle, and they marched to York the following day (Monday the 30 March) - so who gathered up the dead and dug the graves?

It is clear that battlefields, apart from being appalling places to inhabit during and after the event, were lucrative places to acquire loot. This would have been a great opportunity for local scavengers and gravediggers to make money, and the writer Sir Thomas Malory (1415-1471), who may have witnessed battles during the Wars of the Roses, attests to this being common practice by the winning side. He also writes that after battles were over commoners were stripped naked of armour, valuables and belongings and left to rot - especially if the victorious side needed to urgently move on (as did the Yorkists in 1461).

Therefore, in my opinion, only a few thousand (predominantly Yorkist bodies) were buried after the battle of Towton ended, while others, mostly unnamed Lancastrians, were left to decompose naturally in the fields. Villagers would have cleared rivers, but judging by the trial of battle, the time of day, and the miserable weather conditions at Towton in March 1461, this would explain why a smaller ‘physical’ amount of bodies were buried overall (8,000 men according to one contemporary source).

However, it is clear from the decree of Richard III that a mass of bones was reburied in Towton village, and these are likely to have been put in pits in the cemetery adjoining the now lost Towton Chapel.

Evidence proves that there was an earlier chapel and cemetery at Towton long before 1461. Recent research by the Richard III Society unearthed the existence of a papal bull, dated 6 November 1467, which tells of a partially abandoned and ruinous chapel in the village that Edward IV intended to renovate so that services could be held there for the Towton dead. The chapel was dedicated to St Mary, and this is in keeping with the dedication that later became attributed to it. It seems that this original manorial chapel was free-standing and had a small cemetery where some of the slain were buried after the battle. In 1472 there was even a chaplain assigned to manage it, but evidently, the renovation was not finished, and alms were being used to try and upgrade its status - a sad indictment of Edward’s former willingness to commemorate the dead of both sides for political and religious reasons.

The next piece of evidence relating to the Towton Chapel is in the register of grants of the Duchy of Lancaster. The revealing passages prove that there once was an original chapel at Towton and that Richard III was clearly interested in it. After identifying the battlefield, the great armies engaged there and that his brother won the victory over those that had rebelled against him, Richard decreed that £40 was to be provided for the construction of it out of the revenues of the Honour of Pontefract. The details of the building work were entrusted to his, ‘trusty and well-beloved servants Thomas Langton and William Sallay’, the latter being then lord of Saxton who provided the bells for the parish church. The Langton family owned the limestone quarry at nearby Huddlestone and it appears that the Multon family, kinsmen of the Dacre’s of Gilsland, were also involved in the chapel and its foundation.

We can be sure that this Towton Chapel (probably built on the same site as the original) was made of the local stone although the actual design is unknown. In fact, there is no mention in contemporary documents where either of these chapels were actually sited. Still, the antiquary, John Leland, saw ruins of a ‘great chapel’ in about 1540 and he recorded it in his Itinerary of 1558 as being erected where many men slain in the battle were once buried to the north of Towton village. Leland also mentions that John Multon’s father laid the chapel's first stone in a commemoration ceremony that may have also coincided with the adornment of Lord Dacre’s tomb in Saxton churchyard.

Therefore we must assume that Richard’s chapel was not an insignificant building, that it was a large free-standing edifice like the first with new foundations, sumptuously built, and it was in a prominent position that was relatively close to the London Road. This tends to support Leland’s description, and given that he noted it in his work, it is clear that any further archaeological work needs to concentrate on a building much larger than previously thought. The obvious examples of the local chapels at Lotherton and Lead may be taken as probable architectural styles, but not necessarily facsimiles of the much greater battlefield chapel at Towton.

Both earlier and later evidence reveals that the original chapel had a cemetery and that Richard III ordered the reburial of bones from the battlefield here and in graves nearby. If these were purposely exhumed from the battlefield in about 1484 (twenty-two years after the battle) and re-interred in or around the chapel by the Hungate’s, then we must clarify that these were not the ones found by workmen in the 1996 grave. Confirmation of this fact is that complete cadavers, in situ, were excavated from beside Towton Hall and not a mass of disarticulate bones which might be expected after exhumation and reburial. However, as noted by Leland, it was undoubtedly the Hungate family who were responsible for the clearance of bones from their fields and that the original mass graves, which were certainly there at one time on the battlefield, are a mystery no longer. In short, the graves of the fallen that Richard III mentioned in his edict are no longer there.

After its founding, it is believed that Towton Chapel flourished and by February 1484 a new chaplain had been decided upon. John Bateman was to receive seven marks a year from the wardens of Saxton parish church although it is doubtful that he ever took up the post. The chapel was not yet finished, and civil unrest was once again brewing in the kingdom. The building work was not progressing, and in 1486, after the battle of Bosworth and the death of Richard III, Archbishop Rotherham was offering indulgences to anyone who would give alms to finish off the construction. He reported that,

…a certain chapel has been expensively and imposingly erected from new foundations in the hamlet of Towton, upon the battlefield where the bodies of the first and greatest of the land as well as great multitudes of other men were first slain and then buried and interred in the fields around, which chapel in so far as the roofing, the glazing of windows, and other necessary furnishings is concerned has not yet been fully completed, nor it is likely that the building will be finished without the alms and help of charitable Christians in the diocese. (ii)

In the same year, the Langton family sued in the local court for the theft of 460 tiles from their premises and that these might have been intended for the Towton Chapel roof. However, by 22 December 1502 Thomas Savage, Archbishop of York was still desperately trying to drum up support for the completion of the chapel:

Whereas the Chapel of Towton in the parish of Saxton in which chapel and ground about it very many bodies of men slain in time of war lie buried…now forasmuch as the said chapel is not sufficiently endowed with possessions and rents as to sustain it and have divine service celebrated therein, without the charitable alms of Christian people elsewhere. Whereupon William Archbishop of York hereby granted his license and authority to Dom. Robert Burdet, chaplain, to celebrate divine service in the said chapel, and to the inhabitants of the town of Towton to found a guild or fraternity in the same chapel to the honour of St Mary the Virgin, St. Anne and St Thomas the Martyr. (iii)

In 1546 further grants were offered to those who would assist with donations to the chapel's fabric and endowment. Indulgences, ‘of 40 days for 2 years for the newly built Towton Chapel,’ give the impression that patronage was still desperately needed. Earlier offers of indulgences (time off from purgatory) had been largely unsuccessful, but among the grants made in September 1511 was one to Henry Lofte (hermit) of the order of St Paul who purchased several indulgences,

…of the Chapel of St James of Tolton [one of Towton’s original names] in the Parish of Saxton, Co. York, to the intent that he shall leave the said pardon and pray for the king and queen consort and the souls of the late king and queen.’ (iv)

With a new king on the throne and Richard III branded a villain by this time, it was probably thought that the chapel could be put to better use as a chapel of ease. However, even promises of indulgences did nothing to induce further investment or interest in the building work. Evidently, the fact that the Tudors were in power dissuaded many wealthy people from acting and despite several attempts at regeneration the chapel soon became a political embarrassment. After all, the founder was a ‘child killer and tyrant’ by this time and even though many Lancastrians may have had deep feelings for those soldiers who perished at Towton the overriding factor appears to have been against any kind of formal commemoration.

John Leland’s final glimpse of the ruin in the 1540s is evidence that the chapel was certainly a resilient creation despite its traumatic history. We may safely assume that the edifice was cannibalized for building materials soon after this and in later years was used to extend a rapidly expanding Towton Hall. Admiral Hawke was responsible for some of the building work there in about 1776 and various features, including the Chapel Room, substantiate the claim that this part of his house was renovated with reclaimed stonework. With a chimney of brick as evidence of later construction, we may conclude that this extension is not the great free-standing chapel that Leland saw in the 1540s and therefore not the edifice commissioned by Richard III. Further evidence can be brought to bear if we consider that the trench graves discovered in 1996 were found partly under this room continuing past the hall’s north wall into the void and under the chimney. The so-called ‘wall of dead’ and stonework found abutting the cellars in 1797 also confirms the limits of the original fortified manor house of Richard II, and along with the skeletons found in 2006, this further confirms that graves were originally dug beside the hall in 1461 and not in it.

All this indicates that for some time after the battle of Towton, the dead were remembered. The chapel had a social, cultural and religious place in local minds, and for many years after the battle, it was a focal point of commemoration for the Yorkist kings (Edward IV and his younger brother Richard III). Indeed, many efforts were made to finish the building work off by the Tudors and endow the chapel with the materials needed to make it flourish. Therefore we may be sure the battle and those that fought in it were remembered at least by the local (Lancastrian) population who remained partizan and rebellious well into Henry VIII's reign.

It is easy to wax lyrical about such things and assume that the Yorkists had an overriding personal urge to commemorate those men who lost their lives at the battle of ‘Palm Sunday Field’. To overplay the pious nature of medieval monarchs is still a common line for some today. However, the reality is far more in keeping with such foundations in the fifteenth-century, and the need to advertise power and reconciliation were important keys to understanding why the Towton Chapel was conceived. In an age when piety was linked with propaganda, the reasons are comparable with why other ecclesiastical buildings were erected on British battlefields. No doubt the ‘lytyll chapell’ at Barnet was established by Edward IV primarily to heal the deep divisions within his kingdom after the recovery of his throne in 1471. A much earlier church and college founded at Shrewsbury in 1408 was not only built as a memorial to the slain but also to advertise Henry IV’s ability to put down insurrection. At St Albans, after the battle of 1455, funds were made available to pay for prayers to be sung in the abbey for the nobles who had been deliberately killed at the onset of the Wars of the Roses.

Such memorials were magnets for pilgrims and those who wished to make a political statement, and the latter was undoubtedly the aim of Richard III when he became king in 1483. He took the opportunity to commemorate the bloodiest battle of his brother’s reign while at the same time celebrating the precise moment when the Yorkist dynasty was founded. The battle of Towton was also fought in the north of England, which was periodically Richard’s adopted home and his pool of military support in times of crisis. Therefore the foundation of a chapel, to commemorate both Lancastrian and Yorkist losses, was one way of gaining allegiance from wavering nobles when his newly acquired power was still unstable. The fact that the Towton commemorative chapel was built so close to the main road from London to York also proves that Richard was out to create a win-win situation on one of the main arteries of the kingdom.

The chapel and the true fate of the Towton dead may continue to remain an enigma mainly due to Tudor propaganda and the passage of time. However, if the search is to continue any further, archaeology must concentrate on the elusive Chapel Garth ‘to the north of the village’ as mentioned in Drake’s Eboracum, although exactly where this enclosure is today remains a mystery worthy of further illumination.

(i) & (ii) L. Boatwright, M. Habberjam, P. Hammond, Ricardian Bulletin, Autumn, 2007, 20.

(iii) W. Wheater, The History of the Parishes of Sherburn & Cawood, 1882, 70.

(iv) G.E. Kirk, The Ricardian, 1960, 48.