On the 620th anniversary of the battle of Homildon Hill, I thought I’d share some thoughts with you about this important border conflict fought on 14 September 1402. The following extract is taken from my new and updated paperback - Hotspur: Medieval Rebel - soon to be published by The History Press and available to pre-order now.

A Strange Alliance

The battle of Nesbit Moor signified not only a change of fortune for Sir Henry Percy - called Hotspur - and the men of the English border garrisons, but it also dealt a severe blow to Scottish pride – a fact that was bound to result in a significant border reprisal before the end of the 1402 campaigning season.

Today, little evidence survives of what occurred at Nesbit Moor on 22 June 1402, but according to sources, a small English force, commanded by Hotspur and George Earl of Dunbar, attacked a Scottish raiding party under the command of Sir Patrick Hepburn as it tried to gain the relative safety of the River Tweed. According to a signet letter of Henry IV’s council, the Earl of Northumberland, who was then warden of the west march, dutifully informed the king of the resounding English victory:

30 June 1402. Market Harborough. To the Council.

The Earl of the March of Scotland [the Earl of Northumberland] has informed the king that he and his son with the garrison of Berwick-upon-Tweed to the number of 200 have defeated 400 Scots. John Haliburton, Robert Lewedre, John Cokbourne and Thomas Haliburton, Scottish knights, were captured, and Sir Patrick Hepburn and other Scots killed and taken to the number of 240. There is also news from the letters of the Earl of Northumberland, and reports from the bearer of these that 12,000 Scots have been near Carlisle but have done little damage. The earl says that the Scots are proposing to enter the kingdom with so great a power that it appears that they wish to give battle. The council is required hastily to examine arrangements with Northumberland and his son, and to ensure that no harm comes to the marches through their negligence.

Predictably above letter seems to attribute the English victory at Nesbit Moor to the forces of the Earl of Northumberland and Hotspur, even though other sources agree that George Dunbar was also present at the battle. However, some sources record that the Earl of Northumberland was absent and was still languishing in the west march since it was he who had gained firsthand knowledge of the large Scottish army threatening Carlisle and had sent word of this to Henry IV by special messenger.

As for the renegade Scot, George Dunbar, he was almost certainly with Hotspur on this occasion bearing in mind that he had a score to settle with both Archibald Earl of Douglas and Sir Patrick Hepburn over land rights. Moreover, Dunbar knew that lately, Douglas had won over to his side many of his own former vassals, including Hepburn, who naturally saw Dunbar’s absence in Scotland as an opportunity to confirm a measure of independence with the Scottish king. With such a chance to redress the balance a distinct possibility, it is doubtful that Dunbar would have missed such an ideal opportunity to punish those who had recently taken it upon themselves to overrun his ancestral lands.

As for Hotspur, he was more directly affected by Hepburn’s punitive raid. As acting warden of the east march, he was responsible for its safety, and in this respect, he was probably more than willing to join Dunbar in his own hunt for justice so that order might be preserved. After all, who better to advise Hotspur on the best way to confront the Scots than a native lowlander? Given how difficult it had been to engage the Scots and bring them to battle on many previous occasions, Dunbar’s assistance would have been invaluable. Indeed, it is highly likely that the earl had a lot to do with how victory was achieved over his former countrymen at Nesbit Moor. The death of Sir Patrick Hepburn on the field of battle, and the capture of Dunbar’s other ex-tenants and councillors, must have been sweet revenge for the humiliations he had suffered the previous year.

Dunbar’s more obvious usefulness in English ranks was also to be repeated in many other border fights. However, apart from his role as a military adviser, the wayward Scot seems to have been somewhat of an embarrassment to many English commanders, even possibly to the Earl of Northumberland, who may have seen him as a direct threat to his own territorial ambitions in Scotland. Hotspur had previously worked well with his Scottish ally, so doubtless, he recognised that a clear advantage could be gained by having Dunbar’s assistance in military matters. Dunbar’s ability to anticipate his former allies’ strategy; his skill in knowing how and where the Scots might strike next; his capacity to predict what roads they might use to launch their raids into England; and, more importantly, his knowledge of how to confront their bristling schiltrons in open battle, were therefore great assets to established English strategy. Hotspur was the perfect light cavalryman, impetuous and courageous to the extreme, but Dunbar was a prudent tactician of the first order, and in English ranks against his own people, he was to prove a formidable opponent, not only at Nesbit Moor but also a few miles further south on the slopes of Homildon Hill against a more formidable opponent of old.

Indeed, with the Scots punished for their recent incursion into England and Sir Patrick Hepburn lying dead in the heather, Archibald Douglas (called The Loser) could not have been expected to remain idle for long. Infuriated by the recent glut of border inactivity, he soon sought revenge upon the men responsible for slaying his friend. Upon hearing news of the bloodbath at Nesbit, the large Scottish army threatening Carlisle immediately transferred itself from the west to the east march and very soon set about raiding deep into Northumberland.

Douglas - No Loser

Hotspur probably knew that the Scottish army – variously estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000 men – had crossed the River Tweed in early September 1402, and after raiding as far as the River Tyne, it was anticipated that it would be on its way home by the middle of the month. Attending Douglas were his own tenants from Galloway, men from the west and middle marches, Clydesdale and Lothian. Under his banner of the bludy hert rode George Dunbar’s brother, Patrick of Biel, two of Dunbar’s principal Berwickshire vassals, Adam Gordon and Alexander Hume, and George Earl of Angus with his kinsmen from Liddesdale. Douglas had also called in a favour from the Duke of Albany, his former partner in crime and now Scottish regent, and he had responded favourably by supplying Douglas with a retinue of knights led by his heir Murdoch Stewart, Earl of Fife. Also present in the Scottish army were the earls of Moray and Orkney, the lords of Montgomery, Erskine and Grame, along with veterans of Otterburn, including John Swinton, the renowned crusader John Edmonton, and William Stewart. A contingent of thirty French knights was also present in Douglas’s ranks, all eager to strike a blow at the English while peace treaties were being argued over in Paris.

The considerable muster of men who flocked to Douglas’s standard in 1402 is a testament to his emergence as a military leader and a clear indication of how far some Scottish nobles would go to punish traitors, in this case, George Dunbar, Earl of March. The usual campaign of pillage and destruction had its attractions for many ‘small folk’ in the Scottish army, and, undoubtedly, striking a blow at the English for purely selfish reasons was a major consideration for many of those nobles who did not come directly under Douglas’s ever-broadening sphere of influence. However, it must be said that overall, the Scottish army of 1402 was a more unified force than ever before, although its size, probably no exaggeration at some 10,000 men, was always going to become unwieldy and vulnerable to a better-organised English army with archers in the open field.

According to the chronicler Andrew Wyntoun, the Scottish army penetrated as far as Newcastle, plundering towns, burning crops and killing Englishmen on a wide front, and although its exact route into Northumberland is not known, it is safe to assume that the main body of Douglas’s army probably crossed the River Tweed at Coldstream. After extensive raiding in England, the likelihood is that Douglas attempted to follow this same road back into Scotland via Wooler and the valley of the River Till. However, this cannot be established beyond doubt due to conflicting evidence.

George Dunbar’s skill in anticipating the movements of his former kinsmen would now be employed to good effect. Moving ahead of the Scottish army, which was almost certainly hampered by a vast amount of plunder, Dunbar advised the Percys where best Douglas might be apprehended. The place chosen for the concentration of English forces was Milfield-on-Till, six miles northwest of Wooler, only a few miles from the bloodstained moor of Nesbit, where the bones of the dead probably still peppered the ground. However, the Percys’ strategic position at Milfield was not seen as defensive, nor was it considered to be the final battlefield where the two armies might meet. Quite simply, the English position blocked the main road into Scotland and the crossing of the River Tweed at Coldstream. Confronted by such a formidable obstacle as an English army in the open, Dunbar anticipated that the Scots would react in the usual manner. Indeed, as soon as they received word that the English were in the vicinity, Douglas sought advantageous ground of his own choosing.

Homildon Hill

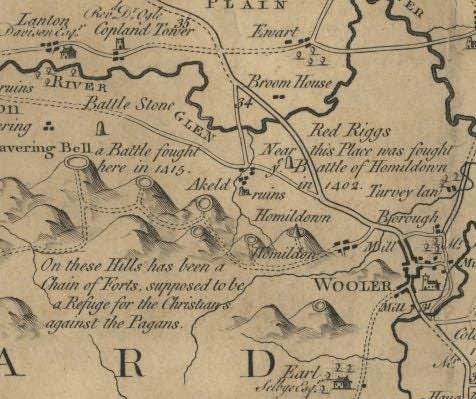

Indeed, immediately after reaching Wooler, Douglas picked the ideal place to stand and fight: a commanding hill to the west of their line of march offered a distinct advantage to Scot’s time-honoured strategy. This was the modern-day Humbleton Hill on the periphery of the Cheviots, almost 1,000 feet above sea level. Thomas Walsingham confirms the site of this significant border encounter in his Historia Anglicana – that is, after railing with his usual egotism against Hotspur’s opponents:

At that time the Scots, made restless by their usual arrogance, entered England in hostile fashion; for they thought that all the northern lords had been kept in Wales by royal command; but the Earl of Northumberland the Lord Henry Percy, and Henry his son, and the Earl of Dunbar who had lately left the Scots and sworn fealty to the King of England, with an armed band and a force of archers, suddenly flung themselves across the path of the Scots who, after burning and plundering, wanted to return to their own country, so that the Scots had no choice but to stop and choose a place of battle. They chose therefore a hill near the town of Wooler, called ‘Halweden Hil’, where they assembled with their men-at-arms and archers.

Marching alongside Hotspur in two divisions was the cream of the northern border garrisons, a large contingent of English border archers and a picked force of knights, all of whom had some personal stake in the coming fight. According to a letter of Henry IV to his council dated 20 September 1402 – which incidentally included a schedule listing certain persons who were ‘not to ransom any Scottish prisoners without instructions from the king’ – some of the knights who rode with Hotspur can be identified. These were the Lord of Greystoke, Sir Henry Fitzhugh, Sir Ralph de Yver, the lieutenant of Roxburgh and the constable of Dunstanburgh. Also present in the Percy contingent were Sir Robert Umfraville, John Hardyng (one of Hotspur’s esquires), and a contingent of traders from Newcastle who were eager to heap revenge on the Scots for their recent plundering of the Tyne valley. The Earl of Westmorland, despite his rivalry with the Percys, had also sent a contingent of men and archers, probably to better stake a claim to any victory that the Percys might otherwise reap for themselves.

John Hardyng, the soldier who later turned historian, relates that he was an eyewitness to the battle, and although he reports almost nothing about the fight itself, he does state quite unmistakably that the Earl of Northumberland was at the battle in person. Indeed, considering one of Hardyng’s stanzas, ‘To Homildon, where on Holy Rode daye, the earle them met in good and stronge araye’, it appears that Hotspur was acting in a more subordinate role to both his father and George Dunbar who, as it turned out, played an integral role in how English strategy was planned.

Doubtless throwing much abuse at the English and George Dunbar – a traitor in their eyes – the Scottish army was in no mood to be frightened from its chosen elevated position. Now crowning and massing its great bristling schiltrons on the slopes of Homildon Hill, there is no doubt that Douglas saw that this superior position offered a distinct advantage over his enemies below him. If his army could only weather the storm of arrows he knew would undoubtedly precede the English attack, it was conceivable to use the gradient of Homildon to launch a downhill charge to break the English line in the water meadows beyond. However, one thing is certain as the English ranks ascended the successive tiers of the Cheviots, Archibald Douglas must have welcomed the opportunity to confront both his mortal enemies in battle at once.

The Battle

As indicated, the Scottish army is said to have numbered some 10,000 men; both Hardyng and the Earl of Northumberland’s letter to Henry’s council confirm this. But how large was the combined Percy contingent in comparison? Firstly, its complement of archers must have been numbered in thousands rather than hundreds, considering that it carried the first phase of the battle so effectively. Naturally, the required number of archers deemed necessary to cause the Scots to quit their defensive position depended on how massed their target was. Considering the size of the Scottish army and its closely packed formations, it may be safe to assume, lacking documentary evidence to the contrary, that the Percy forces were practically wholly composed of archers, as English armies had been during the French wars. Fully mustered, and according to what manpower was available in the northern garrisons at the time, Percy’s army may have comprised approximately 5,000 archers, although the Monk of Evesham estimates the English at 19,000 men, 7,000 of these being archers and the rest men-at-arms. However, a figure of 5,000 would have given the English adequate ‘firepower’ to inflict the maximum amount of damage on the Scots with minimum loss of effectiveness.

Previous experience with the warbow (although known only as a bow at the time) had proved to English commanders that archers had to be counted in thousands to be successful. A hundred or so archers were no use at all on the medieval battlefield, given that they had to deliver as many arrows as possible, as fast as possible, to a fairly narrow area (depending on the formation of the target). The resulting barrage had to be unbearable enough to cause disarray, and this was precisely the outcome if the situation was favourable. Given that at Homildon Hill, the English archers would be shot back at by the Scots, who also had bows – with admittedly less impact due to the imbalance of training, numbers and efficiency – it is safe to assume that the delivery of English arrows would have been as many as six or eight arrows per minute (approximately 5,000 arrows in the air at any one time). With the rate of reloading accepted by modern tests and comparisons, the result of one volley of arrows would be devastating enough, especially if directed at masses of practically unarmoured Scottish levies, to cause terrible casualties. However, English border archers would have almost certainly carried two sheaves of twenty-four arrows on them at any one time, along with those available from their baggage train. It is quite remarkable that the resulting barrage, lasting no more than a few minutes at Homildon Hill, would have the capacity to deliver more than 30,000 arrows to a massed target in one minute, and depending on how many arrows were available after that, a pro-rata figure until arrow supplies were exhausted.

It is not surprising that this clattering ‘hailstorm’ of wood and steel shot in quick successive volleys had attracted George Dunbar’s eye before. The English successes against the Scots at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill were practically recent history in 1402 and no accident in an age when the warbow continued to reign supreme as the principal English weapon of the masses. The bow was especially destructive against unwieldy knots of men and horses, any formation being broken by English archery provided the circumstances were favourable. Certainly, Homildon Hill was one of those more special occasions where, against a mostly unarmoured Scottish army, disarray and death would be dealt within a matter of minutes. The only question that remained in Dunbar’s mind was what would happen if the arrow storm failed to move the Scots off the hill. It was fortunate that in Hotspur, he had the perfect mechanism to deliver the coup de grâce – that is, if he could cool Hotspur’s famous chivalric temperament for just a few minutes longer.

As the marching continued along the Till valley, the waiting game above caused the Scots, in their frustration, to begin blowing their famous hunting horns to unnerve the English. By all accounts, Hotspur was getting increasingly agitated in his saddle. To be at the enemy in true medieval style, head on, with honour, against ‘The Douglas’ was his only wish. All the murky thoughts of moonlit Otterburn, his brother’s wounding, and their inglorious capture undoubtedly flooded back into his mind at this time. In truth, Hotspur probably had already decided to charge the enemy without anyone’s consent, but his illustrious father was riding beside him, and although, according to the Scotichroniconi, Hotspur tried desperately to persuade Dunbar to initiate a mounted attack uphill, he knew that if he even so much as attempted to ride the Scots down single-handedly, there would be hell to pay in the Percy household.

As stated by the English chronicler Thomas Walsingham, part of the English army then ‘left the road in which they had opposed the Scots and climbed another hill facing them’. This smaller hill, also situated on the periphery of the Cheviots, has been identified as Harehope Hill, immediately adjacent to Homildon and to the northwest of it. With a ravine separating the two elevations where, according to Walsingham, the English archers deployed, this leaves only two options for the opening location of Percy’s army. Either the English knights and their archers left the road and took up position on the slopes of Harehope Hill together, their archers being purposely formed in the ravine below to harass the Scottish schiltrons; or alternatively, only the English knights climbed Harehope Hill while their archers took up position below Homildon Hill with their backs to the road. Both options show that archers were detached from their mounted men-at-arms. However, the main question regarding the archers’ opening battle position undoubtedly rests on whether Harehope Hill or the ravine can be considered a suitable place for deploying missile troops, not forgetting the obvious fact that arrows had to reach their target.

In both scenarios, further questions about where the archers would have been most effective must be considered. The Harehope Hill position would have provided a clear height advantage whereby the English archers could have been arrayed in successive lines on the slopes, thereby providing an excellent platform to shoot continuous volleys of arrows across the ravine towards the Scottish ranks massed before them. In the second version, the deployment of the English archers is less important since there is ample room for manoeuvre and for the arrangement of a more traditional formation, given the lie of the land. But in accepting this more favourable position, can we be certain that the archers would have accepted such isolation from their men-at-arms, who Walsingham describes as safely positioned on the hill to their right? Clearly, in both instances, other dynamics need to be analysed to solve the problem.

Establishing range efficiencies is easily done. Modern replica warbows of yew of 100- to 120-pound draw-weight, using 4-ounce war arrows of approximately 30 inches long, can be shot 240 yards with great accuracy. This fact, though, does not consider that most medieval archers had been drawing heavy warbows from an early age, so it is safe to assume that even greater distances and rates of ‘fire’ could be achieved by archers who probably saw the bow as a natural extension of their body. However, with these mechanics in mind (and ranges established between 240 and 300 yards), only one of the above positions can be logically accepted. The ravine between the forward slopes of Harehope and Homildon Hill is approximately half a mile across, clearly not a distance achievable by a medieval bow and arrow. Also, to place archers below Harehope Hill is not a logical battle position, given that this would have put them at a grave disadvantage considering the impetus of a downhill charge by the Scots from Homildon. However, the second position to the northeast tends to favour massed archery, deployment (the necessary embodiment of men to cause maximum destruction in the field) and the accepted ranges of the warbow. It also agrees with the support offered by those English men-a-arms deployed on Harehope Hill, who were obviously mounted and could attack the Scots if they decided to charge down the archers. Moreover, this second battle position also agrees with what the chroniclers say occurred next (the only evidence we have of the events described).

‘A Storm of Rain’

If the English archers formed up before Homildon Hill in the ‘dale’ described by Thomas Walsingham, then the first thing they would have had to do was to move into range of the Scottish army. Obviously, it is impossible to tell what the weather conditions were like on 14 September 1402, but what is known is that the topography of Homildon Hill would have caused a slightly detrimental effect on the range of the warbow, owing to the steep gradient. Swarming in a great sweeping mass halfway up Homildon’s grassy slopes, the English would have first emptied their arrow bags and leisurely set about planting their missiles point down in the ground. On the other hand, the Scots must have been extremely wary of what was about to occur approximately 240 yards below them. Most of Douglas’s men would have likely seen an English arrow storm before, but none dared quit their position in the face of the enemy. Above all, they knew that if they turned their backs, then the Percys, their knights, and their men-at-arms poised on Harehope Hill would most certainly attack. All they could do now was stand behind their shield wall and wait for the deadly, drawn-out hiss to fill the air.

Homildon Hill is terraced in three tiers. The lowest tier, comprising the road, the battle stone (traditionally known as the Bendor Stone) and the low-lying land – later given the name Red Riggs – are features that figure predominantly in local legend, the latter area attributed to the final act of killing in the water meadows of the Till valley. The second tier of Homildon is situated about 100 metres above the road, and this is probably where the English archers took stock of the situation and finally stood to shoot their first volleys at the Scots. The final tier is the summit 200 metres above this at a height almost 305 metres above sea level. There was likely a good distribution of trees on the lower and second tiers of the hill, although this is almost impossible to confirm today. But doubtless, the English captain of archers found that the second tier of Homildon would provide his men with the best possible view of the enemy schiltrons and, therefore, would have instructed his men accordingly to adopt the best position from which to enfilade the Scottish ranks. As for Hotspur, the Earl of Northumberland and George Dunbar – the last of whom had undoubtedly contrived the English strategy to best outwit his countrymen – they too, like their enemies, could only await the outcome of the arrow storm, harnesses and armour rattling, in anticipation of a favourable outcome.

The opening barrage of archery probably lasted only a few minutes at the most, but this provoked an immediate response from the Scots. Thomas Walsingham confirms that:

Without delay, our archers, drawn up in the dale, shot arrows at the Scottish schiltron, to provoke them to come down. In reply the Scottish archers directed all their fire at our archers; but they felt the weight of our arrows, which fell like a storm of rain, and so they fled.

Scots Chivalry - its Finest Hour

Scattering over the perilous reverse slopes of Homildon Hill, the ensuing panic to be free of the deadly hail would have immediately created huge holes in Scottish ranks, especially where a proliferation of English archers meant that proportionally increased casualties would occur. Men injured by many arrows protruding from their heads, limbs and upper bodies would have been instantly incapacitated where they stood, while great heaps of dead and dying would have no doubt built up on the lower slopes of the hill because of the shock and sheer force of the heavy war arrows. For the ‘small folk’ in the Scottish army, the battle was over almost before it began, but Archibald Douglas and his blood allies had clearly not had enough of the slaughter:

So [Douglas] seized a lance and rode down the hill with a troop of horse, trusting too much in his equipment and that of his men, who had been improving their armour for three years, and strove to rush on the archers. When our archers saw this, they retreated, but still firing, so vigorously, so resolutely, so effectively, that they pierced the armour, perforated the helmets, pitted the swords, split the lances, and pierced all the [Scots’] equipment with ease.

In a rush to ride down the English archers, the Earl of Douglas was hit by a great cluster of arrows that punctured his elaborate armour at least five times. John Swinton, called by some the instigator of the Douglas charge, was killed outright, not far from his speeding master, while the impetuous Scottish attack carried forward until it was brought to an abrupt halt in a tumbling mayhem of screaming horses and broken bodies. Their men-at-arms never penetrated the English line. Indeed, those who attempted it were most likely severely wounded and soon finished off or captured behind the lines. Veering away from the plummeting arcs of hissing arrows, most of Douglas’s mounts would have instinctively tried to flee, but as the English retreated before them down the hill, loosing their great warbows in frantic rage, there was no escape for the Scottish knights, owing to the momentum of their charge, the gradient of the hill, and the concavity of the archers’ formation sweeping around their flanks.

The penetrative power of the medieval arrow has been tested against armoured surfaces with impressive results. Those arrows used by the English archers at Homildon Hill probably fell into two categories: the bodkin type of varying lengths, shapes and weights, and the barbed type incorporating a swept-back tail, obviously more difficult to extract in the heat of combat. The arrows which punctured the armour of Archibald Douglas were probably of the former type, shot at an angle of approximately 90 degrees to the surface of the metal at a range of about 70 yards. Heavy war arrows in this category would have impacted Douglas’s body with some considerable force, probably catapulting him out of his saddle. They would have pierced his armour and his body beneath, again depending on the angle of trajectory; the greater the angle of incidence, the less chance of penetration. Douglas also lost an eye in the charge, which might have been attributed to an arrow ploughing through the sight hole of his helmet and into his eye socket beneath, although this, of course, is hard to confirm.

However, the outcome for all those knights who charged down the slopes of Homildon Hill would have been the same: confusion, disarray or death. There was no escape from the barrage of arrows. Even if an individual was not hit directly, at point-blank range, or by ricocheting arrows, there was always a chance that his practically unarmoured horse would be, resulting in the same degree of confusion and death from broken backs and necks. Incapacitation in such a horrific situation clearly led to eventual capture, and Douglas, lying stunned and bleeding on the ground, was about to succumb to the privilege of his class.

According to Thomas Walsingham, at this point in the battle, the rest of the Scottish army fled the field, ‘but flight did not avail them, for the archers followed them so that the Scots were forced to give themselves up, for fear of the death-dealing arrows’. No doubt Hotspur and the English men-at-arms, seeing the rout was on, had already spurred down the slopes of Harehope Hill to take advantage of the situation. However, they would have been disappointed by what they eventually saw in the dale below. Admittedly, they may have taken great joy in hunting down and rounding up Scottish fugitives in the area known later as Red Riggs, but the English warbow had already done its deadly work by sweeping the field of resistance. Walsingham recounts that ‘no [English] lord or knight received a blow from the enemy, but God Almighty gave the victory miraculously to the English archers alone and the magnates and men-at-arms remained idle spectators of the battle’. In fact, casualties were almost non-existent on the English side. Six days after the battle, when Henry IV’s council received news of the English victory, the unbelievable incidence of casualties proved that the Percys had not only won a great victory but that they had also captured:

The earl Douglas, Murdoch of Fife, the earls of Moray, Angus and Orkney, lord Montgomery, Thomas de Herskyn, John Steward of Ernermeth, lord Seton, William Grame, and other knights and esquires amounting to 1,000 persons, Scots and French. Lord Gordon, John Swynton, knight, and other Scots and French were killed, with a loss of only five killed on our side.

Considering the confusion and uncertainty on the medieval battlefield, this seemingly ridiculous English casualty figure illustrates quite graphically that the battle of Homildon Hill was one-sided – almost a massacre. Nearly all the principal Scots leaders had either been mown down by arrows or had been captured by their enemies in no more than an hour. Moreover, the nucleus of Douglas’s ‘militant’ army had almost ceased to exist or been allowed to fall into enemy hands, and the impact of the battle was, to say the least, traumatic.

So, Who Won the Battle?

It is said that 500 Scots were drowned in the River Tweed when they were harassed by the English to their deaths, while Thomas Walsingham, in his closing description of the battle, confirms the death toll and lists those who were captured, along ‘with many other knights to the number of eighty, in addition to the squires and yeomen, whose names are unknown’. In short, Homildon Hill was hailed as a resounding victory for the Percys in the north. They had finally achieved a substantial win over the Scots that could be celebrated as their own. But were these facts all true? After all, did the glory not belong to George Dunbar? What did Hotspur, for example, make of Dunbar’s curt decision not to allow him to charge the enemy with chivalric honour? In fact, how did Hotspur respond to the whole idea of being overruled by a former enemy?

Although we cannot confirm Hotspur’s actual feelings at the time, he must have acknowledged with explosive (and hesitant) speech that the English arrow storm had been a great success. The arrow-riddled battlefield, won exclusively by the lowly English border archer in his humble peasant garb and iron hat, was proof yet again, if further proof were needed, that the power of the warbow and the cloth-yard arrow was an unbeatable force if used against massed targets from defensible positions. The Scottish close-order schiltrons had provided the perfect archery ‘butt’ for well-aimed arrows, while the English knights, probably with increasing frustration, had been restrained from achieving what was exclusively theirs by right on the field of honour. With no other option open to Hotspur but to stand and watch an object lesson in troop harassment, tactical retreat in the face of the enemy, and brilliant point-blank marksmanship, here was confirmation once more that medieval cavalry actions were fast becoming a thing of the past. Although Hotspur and his followers no doubt took part in the pursuit from the field, it is doubtful that any English knight or man-at-arms was happy with the situation. Apart from personally capturing the wounded Douglas and other Scots who Hotspur was later to hold for ransom, the battle of Homildon Hill had been quite simply a non-event as far as chivalry was concerned.

We can almost see the fiery Hotspur in our mind’s eye, straining forward in his saddle, considering every detail of the battle unfolding below him, fingering the hilt of his favourite sword feverously and flashing an eager eye at his father, hoping to see some sign of weakness that might allow him to charge ‘The Douglas’ and his impetuous knights before the lowly English archers stole his thunder. Hotspur probably felt cheated by all the pent-up frustrations brought on by inaction. He, likely as not, knew that French knights at the battle of Crécy had ridden down their own archers to get to grips with the enemy. He also appreciated from experience that as support troops, archers were indispensable on the battlefield. But, as far as real battle was concerned, the warbow was certainly not a chivalrous tool of the trade, nor was it bold enough to match honour with honour on the battlefield. How wrong he was.

As the residue of the flower of the Lothians melted away into the Cheviots and their tenants floundered, drowned and died in the fast-flowing River Tweed, John Hardyng, a witness to Homildon Hill, recounted his version of what fate befell many Scots soon after the battle was over:

Six earles taken and xl thousande plainly, some fled, some died, some maimed there for ever, that to Scotlande agayne than came they never.