A horse, a horse...bury me with my horse!

The tomb of Lord Dacre of Gilsland and the Battle of Towton

This cut-down article comes from my new updated book ‘Towton 1461: The Anatomy of a Battle’ which is available later this year published by The History Press.

After the battle of Towton on 29 March 1461, many mass grave pits were dug on the battlefield (and the immediate vicinity) to bury the dead. But one grave, in particular, stands out from the rest as unique to medieval history, and I thought it might be worthwhile to resurrect the extant information about it, dispel a few myths, and unpick a legend that has baffled historians for at least two centuries.

The rectangular stone tomb of Ranulf Lord Dacre of Gilsland lies to the north side of Saxton ‘All Saints’ Church in North Yorkshire. The church borders the battlefield of Towton, it is contemporary with it, and we may be sure that many other graves were dug here in 1461. Most of these burials were probably Yorkist soldiers. However, after the battle, because this area of Yorkshire was predominantly Lancastrian territory, it is thought that some northerners, including Lord Dacre (and allegedly Lord Clifford), were also buried in Saxton instead of transporting their bodies home.

Lord Dacre (c.1412-1461) was a Cumberland landowner, a peer of the realm, and he and his younger brother Humphrey fought for the Lancastrians at Towton. Like all prominent families in the Wars of the Roses, the Dacre’s had to choose sides in the conflict, and some were killed or attained by the Yorkist regime due to their affiliation with King Henry VI. Ranulf, or more commonly, Ralph Lord Dacre, was almost fifty years old when he died at Towton, and more precisely, it is thought he met his end in North Acres to the left of the Lancastrian battle line. A local legend says an arrow struck Dacre as he removed his helmet to drink a cup of wine. Also, a rhyming couplet that ‘The Lord of Dacres was slain in North Acres’ by a lad in a bur tree is prominent in Towton legend.

So, are these stories really true, or are we dealing with unsupported fact and local myth-making?

Dacre died - that’s a fact, but in my opinion, a fifty-year-old man drawn into the carnage of hand to hand fighting is a man vulnerable to more than just an arrow in the head. Unfortunately, there are many examples of men dying from heart attack, stroke and exhaustion during combat even though their retainers and household men were sworn to protect them. Therefore, given that arrows were available in their thousands on the battlefield after the initial duel, and that Dacre was exhausted in the confines of his armour, then I would say yes, the cause and effect is feasible.

However, Lord Dacre’s brother was a younger luckier man. He managed to escape the battle despite being later attained for treason. His punishment by Edward IV, the victor of Towton, was assured after such a decisive defeat. Therefore who, aside from Humphrey, took care of his brother’s burial and commemoration?

As pointed out, Humphrey was on the run and orders of no-quarter were issued by Edward IV before the battle. Therefore it’s extremely doubtful that any Lancastrian was present on the field when the battle ended unless he was one of the dead or dying. In all probability, Lancastrian executions were also in progress after the event, and we know certain prominent nobles were beheaded by Edward IV in York the following day. So it may have been the impartial heralds who arranged Lord Dacre’s burial (although obviously, the actual tomb in Saxton must have been constructed later (probably in 1468) when Edward IV pardoned Humphrey Dacre for his crimes).

Therefore, let us tentatively apply the factual evidence above and suppose that Lord Dacre’s body was identified on the battlefield sometime during the night of the 29th (or early the next day) when it was safe to do so. The heralds obviously knew of Dacre’s prominence as a knight, and if no one else took time to remove his body from the field, then it is certain they did. They may even have arranged his burial, as they were known for their impartiality and proper observations when it came to all things chivalric.

But taking all this into account, and that Lord Dacre was buried in Saxton churchyard by someone other than his family, what then is a random horse doing in his grave? Can we account for this strange burial in any factual way? Or is this just another fanciful legend of Towton battlefield?

The simple truth is that we cannot be absolutely sure why a horse is buried in Dacre’s grave, or why he was buried (as some say) in a standing position. But rather than accept this impasse, can we hazard an educated guess based on other archaeological evidence; in this case, Anglo-Saxon 6th-9th century human-horse burials that can be verified and closely match Dacre’s legendary internment?

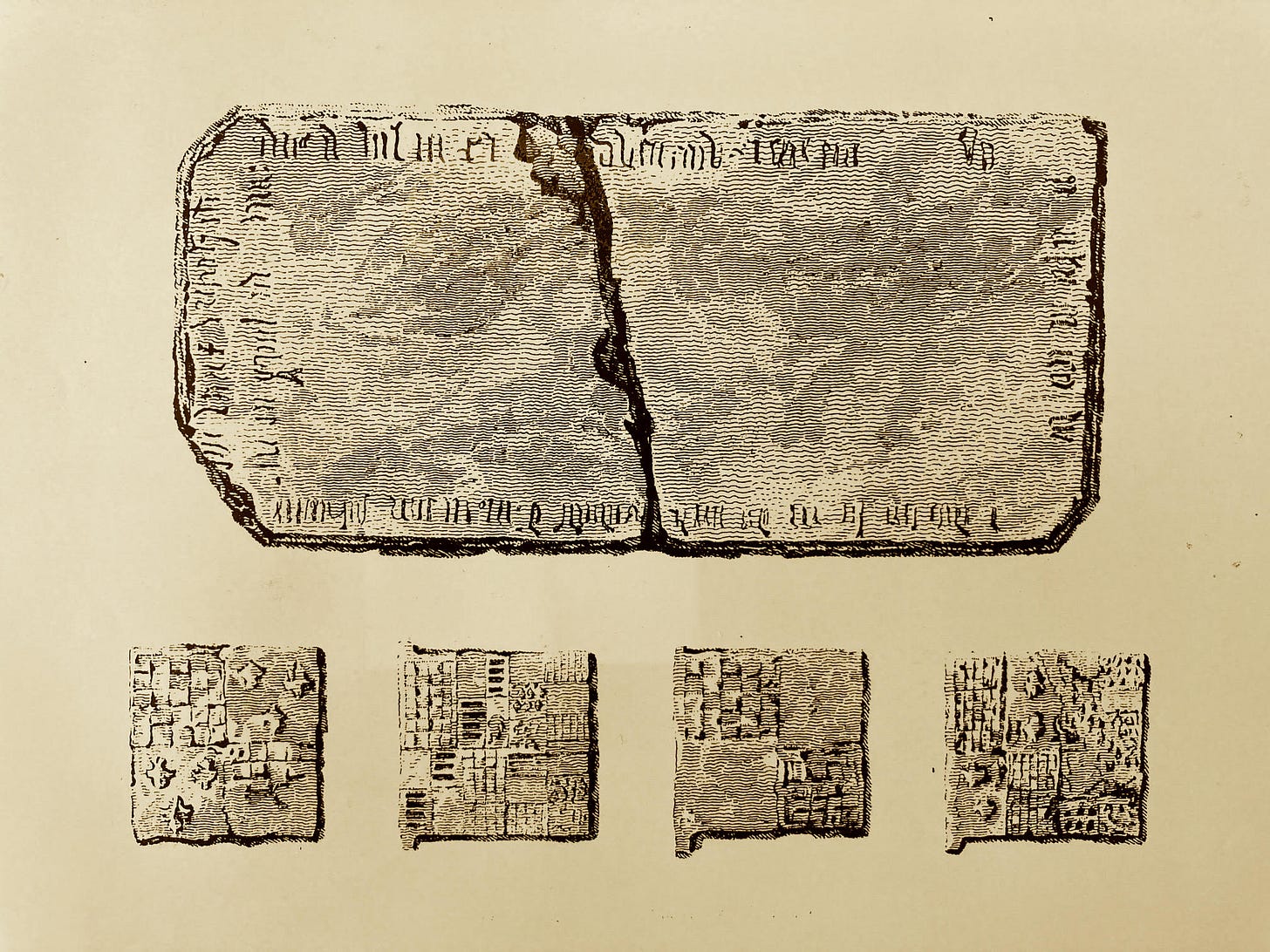

According to recent archaeological evidence, the Anglo-Saxons buried their warrior class with their horses a lot, it seems. One of the many burials at Sutton Hoo is illustrative of this. Another is the one pictured above at Lakenheath. There are others in Britain, and Pamela Cross of Bradford University has done a lot of great work on this subject. Here is an extract from her work in the magazine Saxon:

The behaviour behind these types of burials is complex and much of it appears to have ritual significance. Part of it probably represents feasting residue, part of it sacrificial rites probably associated with fertility and good luck. The human-horse burials certainly seem to have an aspect of status and prestige, but may also have other meanings. Within the Celtic-Northern traditions there are indications that Odin and Frey/Freya, Epona and Rhiannon may figure in horse ritual practices. And more generally, the horse is often symbolically linked both with the sun and with boats. Some feel that the horse represents a means of journeying into the next world, some that it is simply a valuable possession. The actual meanings are probably as multilayered and diverse as the people involved in these practices. 1

In these cases of ritualistic burial, the horse is then a symbol of prestige and power in warfare. Therefore, it is natural to suppose that horses profoundly affected the development of warrior funerary culture in later times. We know this tradition is Anglo-Saxon and had Germanic origins, but did it survive into the late medieval period? After all, the horse was still central to knightly prowess, the culture of chivalry, and the mass heavy cavalry charges of the Middle Ages. Therefore I think a link to a more ancient past is probable given the Dacre evidence.

Given there was little difference between this Anglo-Saxon way of thinking in the Wars of the Roses, are we closer to the truth given that Dacre and his kind generally thought the same way about their horses despite fighting on foot during this period? Another explanation could be that, like some other sites where single horse burials have been found, we could immediately dispel the myth of Lord Dacre and his horse’ in Saxton churchyard by dating the animal’s bones (now in the British Museum) as being much older than previously thought.

To explain this further, Saxton Church dates from the 11th century, but the village itself predates this, appearing in the Domesday Book of 1086. Saxton was formally known as Seaxtun, meaning ‘town or settlement of the Saxons’. Therefore, could we be looking at a bizarre coincidence in the churchyard - namely that Lord Dacre’s burial in 1461 and a single ritual horse burial in the Anglo-Saxon era share roughly the same space? A good explanation, you might think? Well, it would be if we could date both sets of bones!

So what is really under Dacre’s tomb? And is there any other written evidence that this is a 15th-century human-horse burial with Lord Dacre sitting or standing up in his grave?

Curiously, the answer could be yes. Lord Dacre’s strange burial was first reported in 1749 when the tomb had metal clamps securing it, which were later broken into to bury a Mr Gascoigne who was probably related to the local gentry of Parlington, Lotherton and Craignish in Scotland.

While digging this Gascoigne grave - called an abomination by Richard Brooke who visited the site in 1848 - a skeleton was actually found in a standing position. Later, when a further grave was being dug beside the tomb, a horses head was found with its vertebrae extending into Dacre’s grave. A letter dated 23 January 1882 confirms these two burials, although most of the excavations in Saxton churchyard, and later at Towton, were local, amateurish, and not recorded by archaeologists.

However, the letter reads:

My Dear Sir,

When I was at Craignish we had some conversation on the battle of Towton, which was fought in this Parish on Palm Sunday (March 29th Old style) 1461.

I then said that I would try to get hold of a Pamphlet which I had seen on this subject, & let you have it to read. I have not forgotton my promise, but regret that I do not recall where to lay my hand upon this source of information. I have lately had some conversation with the son of the old Sexton who dug the grave close to Lord Dacre's tomb, & who himself was assisting. He tells me that when they had got down about 6 feet, they came upon the skull of a horse, & from the position of it, & the vertebrae of the neck, it was made plain that the body of the horse extended actually into Lord Dacre's grave.

This discovery is a wonderful verification of the tradition in the village that Lord Dacre's horse was actually buried with him in the churchyard. I have in my possession a portion of this skull which I hope some day to have the pleasure of showing to you. The body of the horse undoubdtedly yet lies in Lord Dacre's tomb, as I understand the Sexton did not make any excavations further than were necessary in digging the grave he had in hand.

Ironically the above letter from a Mr George M Webb was addressed to another member of the Gascoigne family, in this case, Colonel Gascoigne, and one wonders at the connection between him and the other more infamous Mr Gascoigne who was so insensitively buried in the same grave as Lord Dacre?

So is Dacre buried in an upright position? And are there any other good examples of this kind of burial in Britain that have no link to other religious beliefs worldwide?

The answer again is yes. At the east end of the north aisle of Bolton Priory Church, North Yorkshire is a chantry belonging to Beamsley Hall, and in it a vault, where, according to tradition, the Mauleverer and Clapham families were all interred upright. The reason for this strange burial custom was said to originate from the Mauleverer family, who refused to bow down to any man even in death. However, in the early 19th century, a custodian of the priory decided to investigate further and look for the family vault. He said:

I knew nearly where the vault must be, so I got some men to dig. We did not strike the vault at once, but after a while we found it, opened it, and there were the coffins sure enough, standing upright, just as the old folk used to say they were. 2

William Wordsworth, the poet, later wrote about Thomas Clapham's son, John Clapham, a participant in the Wars of the Roses, and his poem rings true with the Dacre tomb inscription if nothing else:

A vault where the bodies are buried upright!

There, face by face, and hand by hand,

The Clapham’s and Mauleverer’s stand;

And, in his place, among son and sire,

Is John de Clapham, that fierce esquire,

A valiant man, and a name of dread,

In the ruthless wars of the white and red ,

Who dragged Earl Pembroke from Banbury Church,

And smote off his head on the stones of the porch.

This same John Clapham was a supporter of the Earl of Warwick and took part in the Battle of Edgecote (Danes Moor), fought on 24 July 1469. He was personally responsible for the beheadings of the Earl of Pembroke and his brother near the south porch of Banbury Church. A small, plain rusty sword survives in a branch of the Clapham family today, which may have belonged to John, although this cannot be confirmed.

However, Lord Dacre’s tomb seems to have had a more definite link with the local gentry that existed at the time of the battle. In the 15th century, prominent local families such as the Gascoignes, Scargills, Multons, Sallays and the Hungates (some of who were the lords of Saxton and Lead) would have been clearly interested in Lord Dacreʼs burial - along with the Dacre family, of course, when it was safe to do so. They may have even fashioned the tomb themselves to commemorate the great outpouring of grief for those lost in the Wars of the Roses. It was certainly strong enough even in 1468 to warrant a lasting memorial to one knight who held such staunch Lancastrian sympathies.

We can see these local feelings of loss, pride and commemoration today in the patriotic tone of the contemporary Lancastrian inscription on Lord Dacre’s tombstone. It shouts to us across the ages of a long-forgotten warrior class that had been beaten in more ways than one. The inscription has, over the years, been translated in several ways, but this is my translation which follows Ebouracum fairly closely: 3

Here lies Randolf, Lord of Dacre and Gilsland, a true knight, valiant in battle in the service of King Henry VI, who died on Palm Sunday, 29 March 1461, on whose soul may God have mercy, Amen.

The blackened tomb, about 2½ feet high, displaying Lord Dacreʼs heraldic achievements on four sides, is today in a bad state of repair. Wrenched open, defaced and broken in two pieces by the curious and the disrespectful, it is now ʻprotectedʼ by iron rails and an ongoing mystery. Whether Dacre was buried with his horse, on his horse, or in a standing position are questions that may never be answered. However, the tomb is a unique survival of the 15th century, and as such, it deserves better. Whatever is in the grave (or extending into it), it must not be disturbed. If it ever is, it will be a sad tribute to a man who saw the battle of Towton first-hand and was buried near the battlefield where he lost his life for a cause he believed in.

Saxon, No.55, published by the Sutton Hoo Society, July 2012, p.8

The Claphams of Beamsley, W. H. Fluen, https://williamhenryfluen.de.tl/Claphams-of-Beamsley.htm

F. Drake, Eboracum, 1736, p.111.

This was an amazing read, a truly interesting part of history, built upon history.