Good knight, bad knight?

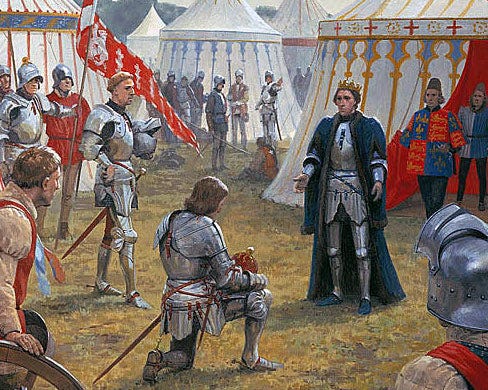

Further thoughts on the unattainable ideals of chivalry in the Wars of the Roses

How could traditional chivalry exist in a kingdom torn by civil war, feuding, treachery and regicide?

In this article, I do not intend to scrutinise the history of chivalry in depth or deliberate when and where it might have taken root in the Middle Ages. Instead, I will deal with how a knight understood the workings of chivalry and knighthood between 1450 and 1500 and how he ‘sought’ to apply this to his life in an age of hollow crowns.

The battle of Northampton in 1460 saw the last time in the Wars of the Roses when a significant attempt to avert bloodshed was made through mediators and heralds before a battle commenced. However, the failure of lofty prelates to negotiate a settlement shows just how far English knights were prepared to go in their quest for supremacy and control of the king.

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487) marked the twilight of chivalry in England, as the brutal struggle between the houses of Lancaster and York shattered the romanticised ideals of knightly conduct. Once bound by codes of honour, battlefield courtesy, and loyalty to king and country, the nobility were ensnared in a conflict where treachery, political pragmatism, and ruthless ambition dictated survival.

Chivalric warfare had once emphasised ransom over slaughter, but the Wars of the Roses turned battlefields into sites of massacre and execution. At Towton (1461), the bloodiest battle on English soil, no quarter was given – prisoners were slain without mercy. Even nobles, once confident in the sanctity of their status, faced execution after capture, as exemplified by the summary killings of Yorkist and Lancastrian leaders after battles like St Albans (1461) and Tewkesbury ten years later.

Betrayal and shifting allegiances also corroded the chivalric ideal of loyalty. The defection of Warwick the Kingmaker, once Edward IV’s staunchest ally, epitomised how power eclipsed honour. By the war’s end, England had transitioned from feudal loyalty to ruthless realpolitik. The age of gallant knights, adorned in shining armour and bound by sacred oaths, faded into legend, replaced by a harsher reality: one where power was not won by honour but by the sword.

But how did it come to this? Was true chivalry always an unachievable ideal? And indeed, were its precise codes followed by one of the most famous chivalric writers ever known?

To begin with, the ‘ideas’ of chivalry were still central to medieval books in the late fifteenth century, and it is from books that the higher classes of society learned the codes and how to use these in practice. By acting chivalrous, the knight hoped to become famous, even a celebrity, seeking honour and virtue among his peers. The search for these qualities was a kind of religion, a way to court respect from ladies, and according to Sir Thomas Malory, the knight-prisoner and author of Le Morte D’Arthur, a crucial (and long-forgotten) expedient to save England from internecine civil war.

King Arthur (the epitome of a chivalrous king) required all his Knights of the Round Table to swear allegiance to a specific code of conduct. This Pentecostal Oath detailed the positive and negative ideals that all Arthur’s knights should not only possess but also live and die by, and it is no accident that this oath was based on the main themes of chivalry known to Malory, a knight himself, in the late fifteenth century:

[He, Arthur] charged his knights never to do outrage nor murder, and always to flee treason, and to give mercy unto him that asketh mercy, upon pain of forfeiture of their worship and lordship of King Arthur forever more; and always to do ladies, damsels, and gentlewomen and widows succour; strengthen them in their rights, and never to enforce [rape] them, upon pain of death. Also, that no man take no battles in a wrongful quarrel, for no love, nor for worldly goods. So unto this were all the knights sworn of the Table Round, both old and young. And every year so were they sworn at the high feast of Pentecost.1

It is well-known that Sir Thomas Malory (d.1471) copied from existing legends of King Arthur and his knights, most notably French versions. Still, this Pentecostal Oath is not mentioned in other Arthurian legends. Only Malory, writing in about 1470, advertised this when William Caxton printed his edition of Le Morte D’Arthur in 1485 (coincidentally, the year of Bosworth and the usurpation of Henry Tudor as Henry VII).

By completely restructuring what had been previously written about King Arthur and his knights, Malory wrote stories that no longer portrayed the clash between earthly and divine issues but focused on personal rivalries and the fall of kings. He incorporated English towns and cities into his stories. His plots contained themes familiar to Malory in real life, whereby some nobles were ambitious enough to kill their opposite number or even exchange one king for another. Moreover, the title of Malory’s work warned readers of a similar tragedy about to unfold in the present, and there is no doubt he was speaking from personal experience of the world beyond his prison cell during the Wars of the Roses.

Of course, many other ordinances of chivalry in the fifteenth century echoed Malory’s hoped-for ideals. Still, most knightly codes of conduct went against the grain of civil warfare. As will be seen, chivalry was a difficult life to follow in the late Middle Ages, and not all nobles followed its rules of conduct to the letter. As an ideal set of rules, the ordinances of chivalry stipulated that, above all, a knight should strive for honour and virtue above all else, at least in the mind’s eye:

Be faithful to God and the king…sit in no place where any judgement should be given wrongfully against anybody to your knowledge. Also, ye shall not suffer no murderers nor extortioners of the king’s people in the country where ye dwell, but with your power ye shall have them captured and put into the hands of justice.2

These were only a few of the unattainable codes of knighthood that even Sir Thomas Malory defaulted against in his lifetime. In fact, Malory – the author of the most chivalric work of the period (perhaps of all time) was, in every way, a hardened criminal.

Before he was imprisoned for the last time in the late 1460s, Malory was likely in the service of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, and over several years, he resorted to a life of crime in full view of his master. Warwick may have tried to protect Malory by packing courts of inquiry with his personal retainers and corrupt judges (although this cannot be proved). Still, when Malory was accused of rape, extortion, kidnap, sacrilegious robbery, theft, and the attempted murder of the Duke of Buckingham in 1451, he cleverly escaped serious punishment. Some of his recorded crimes were never proven, but as they say, there is no smoke without fire, and despite being released and escaping several times, Malory’s luck ran out in 1468 when his cell door was firmly bolted shut for the last time. His backing of Warwick’s rebellion against Edward IV assured his final confinement to the Tower of London and later Newgate prison, where he allegedly composed Le Morte D’Arthur whilst suffering from an unspecified illness.

Malory died in 1471, and the world was utterly ignorant of his great manuscript, but before this, we may have wondered about his life’s work and his reason for writing such a virtuous piece of poetry when his own life was such a contradiction. However, before his misdemeanours took root, Thomas married well, owned land and was politically ambitious. He saw military service in Gascony and was elected a member of parliament for Warwickshire in 1445. He was dubbed a knight, fought and was exposed to literature, as were many nobles in the fifteenth century. However, in the 1450s, a black cloud overshadowed his spotless career, and the Lancastrian regime wanted him permanently locked up. It could have been far worse. When he was released from prison by William Lord Fauconberg in 1460, he may have marched north to fight for the Yorkists. Therefore, it is likely that Malory fought (or witnessed) the battle of Towton in 1461 and the subsequent campaigns to subdue the northern castles in 1462-64.

However, Malory’s freedom was short-lived, and even the Yorkists wished him incarcerated for good when his master Warwick rebelled against Edward IV in 1468.3 Like many other English knights, Thomas was a victim of fortune’s wheel and was well-placed to understand what it meant to be involved in treachery and civil war. It is a wonder he was not executed for treason many times. Malory probably knew that chivalry was a harsh mistress and recognised that its codes of honour were unattainable for most men. The notions of knighthood were high ideals to live up to, and the second half of the fifteenth century was no place for a Sir Galahad, Arthur’s most chivalrous knight.

It may seem quaint today to speak about Arthur’s legends, the codes of chivalry and knightly brotherhood. Still, in medieval times, most knights like Malory constantly strived to attain perfection. To live up to the codes of chivalry was a virtue in itself. Others, it seems, ignored the code even though chivalric ideals were inseparable from religious devotion. This devotion can be seen in heraldic mottos, where nobles hinted at their intentions in life. These were portrayed in heraldic badges and military standards as a reminder of the ideals of chivalry.

One of Richard III’s mottoes as Duke of Gloucester was tant le desieree (I have longed for it so much), which he handwrote at the bottom of a manuscript describing the life of Ipomedon, in his opinion, ‘the best knight in the world’. Richard may have yearned for a time when he could emulate the prowess of his idol and achieve honour and virtue in battle, the greatest accolade of any knightly career. His other famous motto, loyalté me lie (loyalty binds me), also advertised the constant heartbeat of his life, chivalry, and he demonstrated this loyalty to the code several times, even when his brother, the Duke of Clarence, deserted Edward IV and sided with the Earl of Warwick, in 1468.

Richard’s honesty and virtue can be applauded or taken for granted. However, what shines through the medieval half-light is that our most vilified king served his elder brother (Edward IV) to the best of his ability, and contemporaries universally admired his efforts to achieve the chivalric ideal in the face of adversity. However, a man can only do so much, and the chivalric ideal escaped even his lofty ambitions when he organised the regicide of Henry VI in the Tower of London in 1471. Albeit on behalf of his brother Edward, Richard was England’s Lord High Constable and had little choice in the matter.

Like many nobles before him, his longed-for ideal had no place in the Wars of the Roses. Chivalry was dead, and his own attempt at a brief resurgence likely led to his death at the battle of Bosworth in 1485.

The Wars of the Roses marked not only a dynastic conflict that tore England apart but also the twilight of the chivalric ideal that had once bound the nobility in a shared code of honour, loyalty, and martial conduct. In theory, chivalry enshrined values such as courage, courtesy, and fidelity to one's lord. In practice, however, the brutal and shifting realities of the mid-to-late fifteenth century rendered such ideals increasingly untenable. The battlefield was no longer the stage for noble deeds but for ruthless pragmatism, betrayal, and political expediency. The disintegration of central authority and the incessant turbulence of civil war meant that survival often depended less on honour and more on adaptability, opportunism, and raw power.

Many knights and nobles, once paragons of chivalric virtue, found themselves ensnared in a cycle of broken oaths, rapidly changing allegiances, and the need to protect their lands and bloodlines at all costs. The chaos of the conflict blurred traditional loyalties; a lord could be a staunch Lancastrian one year and a Yorkist the next, not always out of duplicity, but in desperate response to shifting fortunes. The very act of switching sides, which in earlier times might have been deemed disgraceful, became a grim necessity. Even the concept of ransom—central to chivalric warfare—was eroded, as political killings, executions after capture, and the targeting of heirs became common.

The ferocity of battles such as Towton and Tewkesbury underscored this shift. These were not engagements governed by knightly valour but by annihilation and vengeance. The battlefield became a place not of gallant contests but of slaughter, often including the wounded and surrendered. In the shadow of such violence, chivalry could not thrive. Men like Warwick the Kingmaker, who once embodied the grandeur of noble power, fell victim to the instability others had helped to create, betrayed by the same forces of shifting loyalty and political chaos they themselves had once manipulated.

Ultimately, the Wars of the Roses revealed that chivalry, though still evoked in pageantry and courtly language, no longer served as a meaningful guide to action. It had become an anachronism, ill-suited to a world where kings could be deposed by their cousins and nobles. Knights had to navigate a minefield of divided loyalties and survivalist choices. Therefore, the death of chivalry was not a sudden collapse but a slow, agonising erosion, brought about by the harsh realities of a fractured realm where ideals bowed before the demands of civil war.

H. Cooper, ed., Le Morte Darthur, 1998, p. 57

H. Arthur, Viscount Dillon, ed., A Manuscript Collection of Ordinances of Chivalry of the Fifteenth Century, Archaeologia, vol. 57:1, 1900, pp. 67-8

P.C.J. Field, The Life and Times of Thomas Malory, 1993.

If you enjoyed this post, leave a comment. In the meantime, if you are a fan of the Wars of the Roses, here are some of my latest books on Amazon. Reviews are always kindly appreciated!

Richard? Loyalty to himself. Rather like Warwick, another man of this era I cannot help but admire. A Neville trait, perhaps? Who can say? Every man with any means, any pull was usually out for himself: such were the times. Good article.